3 Common Sprinting Tips That Actually Make You Slower

Have you ever wondered why, despite trying common sprinting improvement techniques (such as lifting your knees), you’re not really getting any faster?

The human body is very good at “problem-solving.” Think about the first steps a baby takes. Do the parents have to “coach” the baby how to walk? Certainly not. Even with a skill like swimming, young children are perfectly capable of teaching themselves through the process of trial and error over time.

It is, in fact, the process of trial and error that usually leads to the best and longest-lasting results! Too many sports and skills are increasingly becoming over-coached while free play, the best time for learning via trial and error, is decreasing (playing teaches growing athletes a variety of movement skills that the body will easily plug into whatever sport is played down the line).

With sprinting and running in general, we often do more harm than good with the things we tell athletes in an effort to get them to run faster. The three big ones both athletes and coaches would do well to discard from their movement vocabulary are:

- Lift the Knees

- Keep the Elbows at at 90 Degrees

- Run tall!

1. “Lift the Knees”

Although it seems natural to tell athletes to lift their knees while running, realize that lifting the knees to the optimal height for each athlete will happen totally naturally when everything else is on point. Researchers have analyzed the 100m dash world finalists and found that lifting the knees to greater heights does not correlate to faster times.

On the contrary, consciously lifting the knees while running can result in two big problems.

- It can cause an athlete to spend more time with their foot on the ground in order to let the knee reach higher in front of them. More time on the ground is not good in sprinting!

- It can throw off the timing of how an athlete pushes against the ground. They will often push straight downwards earlier in the stride in order to lift the knee up higher

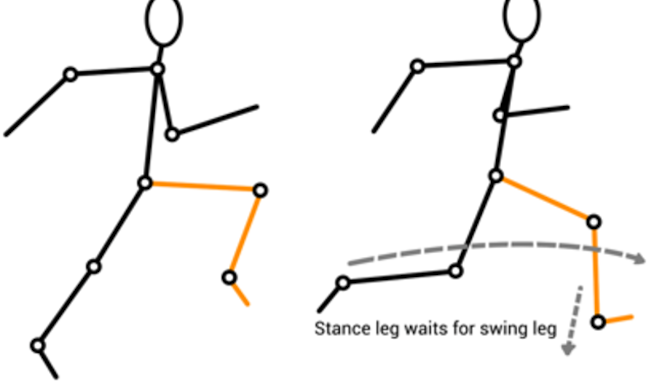

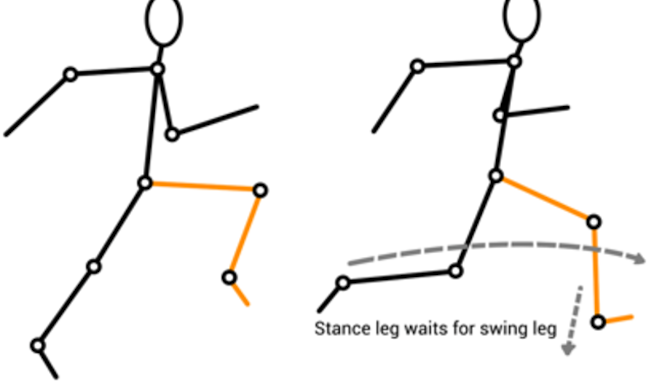

In addition, by lifting the knee high, the swinging leg behind the athlete now has to wait until the foot in front comes down to the ground to complete its cycle. In essence, lifting the knees will lower the stride rate of the athlete, which is particularly bad for team-sport athletes.

In a position of increased knee lift, the swinging leg behind the athlete must wait longer to get to the front and complete the sprint cycle (image from the book “Speed Strength”)

Instead of just believing more knee drive is better, we should instead be paying attention to pelvic posture and control, as well as looking at how much dorsiflexion an athlete naturally produces against the ground (more dorsiflexion will tend to increase knee lift by virtue of increased ground contact time) plus how quickly the foot and Achilles tendon on an athlete store and release energy (faster storage and release will yield a lower knee drive).

“Everybody in sprinting is so stuck on knee lift, knee lift. Getting your knees up high. But no one is focused on the power you need to put back into the ground,” reigning 100-meter dash world champion Justin Gatlin told STACK. “So with that knee up, it’s coming back into the ground. Most sprinters and most coaches don’t emphasize how to be able to plant that foot back into the ground or how to be able to push off that step. So everybody kinda just steps down, and that foot goes dead or that leg goes dead or that stride goes flat, because all they’re worrying about is that next knee going up. So people need to be worried more about the power you put into the track, not so much about knees coming up off the track.”

2. “Keep the Elbows at 90 Degrees”

This is a really common tip given to young athletes that will only have to be undone later in their career. This is what a 90-degree elbow looks like:

The “90 Degree Elbow” concept has many faults, and is a guaranteed way to make athletes slower (image from the book “Speed Strength”)

When running, the angle between the upper and lower arms is constantly changing, and for good reason. The natural opening and closing of the arm is important for optimizing angular momentum in the upper body, as well as helping connect the upper half with the opening and closing angle of the legs. Since the angles of the shins and the thighs are constantly changing when running, and the arm and leg action of sprinting is quite connected, why would we try to fix the arms to only one angle

What would happen if we told athletes to fix the angle of their knees while running? They’d either fall flat on their face or run extremely awkwardly. These photos provide a visual of how optimal arm angle changes throughout the stride:

An athlete performing a normal sprint stride with the arm opening up close to 180 degrees toward the bottom of the stride (image from the book “Speed Strength”)

The arms can certainly be too loose and wild during sprinting, but we tend to over-correct athletes with improper arm action. We don’t want to tie them down into a constricted movement. Using training tools such as the WeckMethod Pulsers is a simple method to clean up arms that seem to be swinging everywhere during running.

In many cases, athletes who have arms that are out of control may just need to spend more time doing general preparation movements such as crawling and climbing. An athlete who cannot swing from monkey bars or crawl effectively likely lacks the ability to “tie” their shoulders to their hips well.

3. “Run Tall!”

This last one is probably my personal favorite, since it is the most commonly used and accepted across the bandwidth of sprint drills and sprinting itself. This is the idea of “running tall.”

First off, great sprinters do tend to run with relatively higher hips than lesser sprinters, but this is largely by virtue of being able to extend the shin out so that the leg hits the ground fairly rigidly. The ability to extend the swing leg in running, combined with a foot that can absorb and release the force of the ground well, is what “run tall” is built around.

With this in mind, simply telling an athlete to “run tall” has two common negative consequences.

- It worsens sprinting posture

- It negatively impacts the fulcrum of the push (the ability to produce good horizontal force)

Running tall can hurt sprint posture, because good sprint posture featured a slightly forward torso lean with the chest and specifically the sternum out ahead of the body. Coach Adarian Barr has pioneered this idea of sprint position, and it impacts everything in athletic movement.

Good sprint posture features the sternum pushing forward in front of the head (Image from the book “Speed Strength”)

When we say “run tall!”, this often manifests itself in the athlete straightening the spine. They lose the advantage of putting their weight in front of their center of mass, which is a must for good sprinting. Running tall also makes the ideal position of the stance leg when the knee is directly under the hip nearly impossible. You want a slight bend in this knee to allow the athlete to direct sprint thrust backwards and propel themselves forward. In the picture on the left below, see how running tall negatively impacts chest position. In the picture on the right below, see how it also causes the push leg to become straighter than it needs to be.

Negative impacts of “running tall” on chest position and stance leg position (Image from the book “Speed Strength”)

The one place where “running tall” could be of use if it is in reference to the hips, not the head, and the athlete responds to the cue with an appropriate swing leg action where the leg almost completely straightens as it approaches the ground but still contacts the ground several inches in front of the athlete without heel striking. The odds that a cue of “run taller!” provided without additional context producing this desired result is slim to none.

More often than not, we end up coaching (or listening to coaching) with the best of intentions, but the results don’t come. In many cases, getting more coordinated and generally fit through basic human movements (such as crawling, climbing, chasing, carrying, throwing, swinging, lunging, etc.) in the median of play can slowly improve sprint technique over time, and do so in a way where the athlete, especially the young athlete, learns on their own (the best way to learn).

That being said, there are a variety of means (such as properly used mini-hurdles) that can have a strong positive impact on sprint technique, both for track and field and team sport athletes. Selective strength work such as extreme-isometrics are another method that can improve sprint technique with no extra “coaching”. If you are interested in more aspects of coaching sprint technique correctly, as well as the strength backing of sprint mechanicsms, check out my new book Speed Strength.

Photo Credit: technotr/iStock

READ MORE:

RECOMMENDED FOR YOU

3 Common Sprinting Tips That Actually Make You Slower

Have you ever wondered why, despite trying common sprinting improvement techniques (such as lifting your knees), you’re not really getting any faster?

The human body is very good at “problem-solving.” Think about the first steps a baby takes. Do the parents have to “coach” the baby how to walk? Certainly not. Even with a skill like swimming, young children are perfectly capable of teaching themselves through the process of trial and error over time.

It is, in fact, the process of trial and error that usually leads to the best and longest-lasting results! Too many sports and skills are increasingly becoming over-coached while free play, the best time for learning via trial and error, is decreasing (playing teaches growing athletes a variety of movement skills that the body will easily plug into whatever sport is played down the line).

With sprinting and running in general, we often do more harm than good with the things we tell athletes in an effort to get them to run faster. The three big ones both athletes and coaches would do well to discard from their movement vocabulary are:

- Lift the Knees

- Keep the Elbows at at 90 Degrees

- Run tall!

1. “Lift the Knees”

Although it seems natural to tell athletes to lift their knees while running, realize that lifting the knees to the optimal height for each athlete will happen totally naturally when everything else is on point. Researchers have analyzed the 100m dash world finalists and found that lifting the knees to greater heights does not correlate to faster times.

On the contrary, consciously lifting the knees while running can result in two big problems.

- It can cause an athlete to spend more time with their foot on the ground in order to let the knee reach higher in front of them. More time on the ground is not good in sprinting!

- It can throw off the timing of how an athlete pushes against the ground. They will often push straight downwards earlier in the stride in order to lift the knee up higher

In addition, by lifting the knee high, the swinging leg behind the athlete now has to wait until the foot in front comes down to the ground to complete its cycle. In essence, lifting the knees will lower the stride rate of the athlete, which is particularly bad for team-sport athletes.

In a position of increased knee lift, the swinging leg behind the athlete must wait longer to get to the front and complete the sprint cycle (image from the book “Speed Strength”)

Instead of just believing more knee drive is better, we should instead be paying attention to pelvic posture and control, as well as looking at how much dorsiflexion an athlete naturally produces against the ground (more dorsiflexion will tend to increase knee lift by virtue of increased ground contact time) plus how quickly the foot and Achilles tendon on an athlete store and release energy (faster storage and release will yield a lower knee drive).

“Everybody in sprinting is so stuck on knee lift, knee lift. Getting your knees up high. But no one is focused on the power you need to put back into the ground,” reigning 100-meter dash world champion Justin Gatlin told STACK. “So with that knee up, it’s coming back into the ground. Most sprinters and most coaches don’t emphasize how to be able to plant that foot back into the ground or how to be able to push off that step. So everybody kinda just steps down, and that foot goes dead or that leg goes dead or that stride goes flat, because all they’re worrying about is that next knee going up. So people need to be worried more about the power you put into the track, not so much about knees coming up off the track.”

2. “Keep the Elbows at 90 Degrees”

This is a really common tip given to young athletes that will only have to be undone later in their career. This is what a 90-degree elbow looks like:

The “90 Degree Elbow” concept has many faults, and is a guaranteed way to make athletes slower (image from the book “Speed Strength”)

When running, the angle between the upper and lower arms is constantly changing, and for good reason. The natural opening and closing of the arm is important for optimizing angular momentum in the upper body, as well as helping connect the upper half with the opening and closing angle of the legs. Since the angles of the shins and the thighs are constantly changing when running, and the arm and leg action of sprinting is quite connected, why would we try to fix the arms to only one angle

What would happen if we told athletes to fix the angle of their knees while running? They’d either fall flat on their face or run extremely awkwardly. These photos provide a visual of how optimal arm angle changes throughout the stride:

An athlete performing a normal sprint stride with the arm opening up close to 180 degrees toward the bottom of the stride (image from the book “Speed Strength”)

The arms can certainly be too loose and wild during sprinting, but we tend to over-correct athletes with improper arm action. We don’t want to tie them down into a constricted movement. Using training tools such as the WeckMethod Pulsers is a simple method to clean up arms that seem to be swinging everywhere during running.

In many cases, athletes who have arms that are out of control may just need to spend more time doing general preparation movements such as crawling and climbing. An athlete who cannot swing from monkey bars or crawl effectively likely lacks the ability to “tie” their shoulders to their hips well.

3. “Run Tall!”

This last one is probably my personal favorite, since it is the most commonly used and accepted across the bandwidth of sprint drills and sprinting itself. This is the idea of “running tall.”

First off, great sprinters do tend to run with relatively higher hips than lesser sprinters, but this is largely by virtue of being able to extend the shin out so that the leg hits the ground fairly rigidly. The ability to extend the swing leg in running, combined with a foot that can absorb and release the force of the ground well, is what “run tall” is built around.

With this in mind, simply telling an athlete to “run tall” has two common negative consequences.

- It worsens sprinting posture

- It negatively impacts the fulcrum of the push (the ability to produce good horizontal force)

Running tall can hurt sprint posture, because good sprint posture featured a slightly forward torso lean with the chest and specifically the sternum out ahead of the body. Coach Adarian Barr has pioneered this idea of sprint position, and it impacts everything in athletic movement.

Good sprint posture features the sternum pushing forward in front of the head (Image from the book “Speed Strength”)

When we say “run tall!”, this often manifests itself in the athlete straightening the spine. They lose the advantage of putting their weight in front of their center of mass, which is a must for good sprinting. Running tall also makes the ideal position of the stance leg when the knee is directly under the hip nearly impossible. You want a slight bend in this knee to allow the athlete to direct sprint thrust backwards and propel themselves forward. In the picture on the left below, see how running tall negatively impacts chest position. In the picture on the right below, see how it also causes the push leg to become straighter than it needs to be.

Negative impacts of “running tall” on chest position and stance leg position (Image from the book “Speed Strength”)

The one place where “running tall” could be of use if it is in reference to the hips, not the head, and the athlete responds to the cue with an appropriate swing leg action where the leg almost completely straightens as it approaches the ground but still contacts the ground several inches in front of the athlete without heel striking. The odds that a cue of “run taller!” provided without additional context producing this desired result is slim to none.

More often than not, we end up coaching (or listening to coaching) with the best of intentions, but the results don’t come. In many cases, getting more coordinated and generally fit through basic human movements (such as crawling, climbing, chasing, carrying, throwing, swinging, lunging, etc.) in the median of play can slowly improve sprint technique over time, and do so in a way where the athlete, especially the young athlete, learns on their own (the best way to learn).

That being said, there are a variety of means (such as properly used mini-hurdles) that can have a strong positive impact on sprint technique, both for track and field and team sport athletes. Selective strength work such as extreme-isometrics are another method that can improve sprint technique with no extra “coaching”. If you are interested in more aspects of coaching sprint technique correctly, as well as the strength backing of sprint mechanicsms, check out my new book Speed Strength.

Photo Credit: technotr/iStock

READ MORE: