ACL Injury Recovery in 4 Phases

You don’t even need to say all three letters. A torn ACL is an injury so devastating, we abbreviate it, calling it just “A.” Tear this tenuous knee ligament and you have a hard road ahead: surgery, rehab and a long recovery. Doctors used to advise patients to wait four to six months before returning to play, but recently they’ve been suggesting a longer waiting period for female athletes—a year, or better yet, two years.

Sound extreme? The docs don’t prescribe this heavyhanded medical protocol without reason. Nearly 30% of athletes coming back from an ACL tear suffer a re-tear, and the risk is even higher for females between the ages of 12 and 18 who return to “high activity” sports—those involving jumping, cutting and stops-and-starts—within the first year.

Researchers attribute the problem to the slow return of proprioception (the ability to sense where the body is in space) within the knee. Athletes often feel this. They tell you there’s a hitch in my motion or my right leg is a split second behind. Unfortunately, more than half of them are unable to return to their previous playing level.

So how do players like Adrian Peterson and RGIII get back up to speed so quickly? The process looks something like this:

- Phase I (surgery – 1 month): Perform therapeutic exercises to recover range of motion.

- Phase II (1 to 3 months): Do gentle strengthening and cardio work. Begin to retrain proprioception.

- Phase III (3 to 4-5 months): Gradual progression in strengthening but no twisting and turning.

- Phase IV (5 to 9+ months): I call this the “Gap Phase,” because it’s when most athletes graduate from physical therapy. Their insurance will tell them they’re done. But good enough to walk to class is not the same as good enough to perform on the field. So despite what therapists or insurance adjusters say, this is when an athlete must really turn it up in order to return to his/her previous level of play.

As a therapist at Fit2Finish, I specialize in working with athletes in the Gap Phase. It’s a critical time in their rehab, and they need neuromuscular training that is specific to their sport. My goals are to teach athletes how to:

- Regain quickness and proprioception

- Balance demands on right and left sides to develop smooth movement

- Re-ignite the neuromuscular pathways mother nature designed to protect the knees

- Develop safer body position for play (bent knees, balls of the feet, head up)

- Build plenty of core strength to stabilize movement

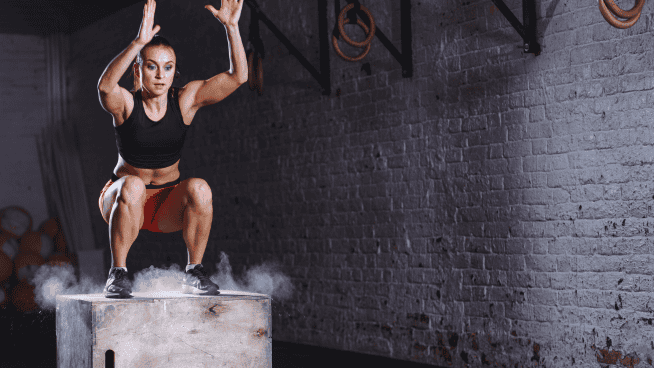

Here’s a look at a training circuit I set up with a high school group, including a cone course for quickness and agility. The cones are easy to set up at home. Start with straight ahead steps, then try it sideways, weaving in and out, slalom, hopping, jumping, bounding and pivoting. Be sure to alternate the lead foot. Remember to be accurate first, then increase the pace. Get it right, then get it fast.

[youtube video=”N48BXxLXU6s” /]Once you have your feet under you, add the ball. Here’s a look at a drill I use with soccer players called Hop and Volley. Start slowly and gain confidence and strength by bounding sideways over the cones. Then, rediscover your “feel” as you volley the received ball with increasing pace.

How do you know when you’re ready to get back on the field? You’ll know you’re there when your doc says yes, your body says yes, and your brain agrees. Be patient, determined and quick. Your hard work will pay off.

Learn more about preventing and recovering from ACL injuries:

- The Athlete’s Guide to the ACL

- Nutritional Guidelines to Optimize ACL Rehab

- Reduce Your ACL Injury Risk

- How ACL Injuries are Detected on the Field

Photo: 101greatgoals.com

RECOMMENDED FOR YOU

MOST POPULAR

ACL Injury Recovery in 4 Phases

You don’t even need to say all three letters. A torn ACL is an injury so devastating, we abbreviate it, calling it just “A.” Tear this tenuous knee ligament and you have a hard road ahead: surgery, rehab and a long recovery. Doctors used to advise patients to wait four to six months before returning to play, but recently they’ve been suggesting a longer waiting period for female athletes—a year, or better yet, two years.

Sound extreme? The docs don’t prescribe this heavyhanded medical protocol without reason. Nearly 30% of athletes coming back from an ACL tear suffer a re-tear, and the risk is even higher for females between the ages of 12 and 18 who return to “high activity” sports—those involving jumping, cutting and stops-and-starts—within the first year.

Researchers attribute the problem to the slow return of proprioception (the ability to sense where the body is in space) within the knee. Athletes often feel this. They tell you there’s a hitch in my motion or my right leg is a split second behind. Unfortunately, more than half of them are unable to return to their previous playing level.

So how do players like Adrian Peterson and RGIII get back up to speed so quickly? The process looks something like this:

- Phase I (surgery – 1 month): Perform therapeutic exercises to recover range of motion.

- Phase II (1 to 3 months): Do gentle strengthening and cardio work. Begin to retrain proprioception.

- Phase III (3 to 4-5 months): Gradual progression in strengthening but no twisting and turning.

- Phase IV (5 to 9+ months): I call this the “Gap Phase,” because it’s when most athletes graduate from physical therapy. Their insurance will tell them they’re done. But good enough to walk to class is not the same as good enough to perform on the field. So despite what therapists or insurance adjusters say, this is when an athlete must really turn it up in order to return to his/her previous level of play.

As a therapist at Fit2Finish, I specialize in working with athletes in the Gap Phase. It’s a critical time in their rehab, and they need neuromuscular training that is specific to their sport. My goals are to teach athletes how to:

- Regain quickness and proprioception

- Balance demands on right and left sides to develop smooth movement

- Re-ignite the neuromuscular pathways mother nature designed to protect the knees

- Develop safer body position for play (bent knees, balls of the feet, head up)

- Build plenty of core strength to stabilize movement

Here’s a look at a training circuit I set up with a high school group, including a cone course for quickness and agility. The cones are easy to set up at home. Start with straight ahead steps, then try it sideways, weaving in and out, slalom, hopping, jumping, bounding and pivoting. Be sure to alternate the lead foot. Remember to be accurate first, then increase the pace. Get it right, then get it fast.

Once you have your feet under you, add the ball. Here’s a look at a drill I use with soccer players called Hop and Volley. Start slowly and gain confidence and strength by bounding sideways over the cones. Then, rediscover your “feel” as you volley the received ball with increasing pace.

[youtube video=”uElyZFL0Tjg” /]How do you know when you’re ready to get back on the field? You’ll know you’re there when your doc says yes, your body says yes, and your brain agrees. Be patient, determined and quick. Your hard work will pay off.

Learn more about preventing and recovering from ACL injuries:

- The Athlete’s Guide to the ACL

- Nutritional Guidelines to Optimize ACL Rehab

- Reduce Your ACL Injury Risk

- How ACL Injuries are Detected on the Field

Photo: 101greatgoals.com