Applying Movement Framework For Athletes

It is easy to get stuck in a rut as a coach. We get comfortable with a series of exercises in our warm-ups and drills and repeat them for years on end. Occasionally we see an exercise that someone else has used, and we copy it. We tend to do what we are familiar and comfortable with and ignore those exercises that are unfamiliar or that we can’t do ourselves. If we limit what exercises we use with our athletes, we limit their potential.

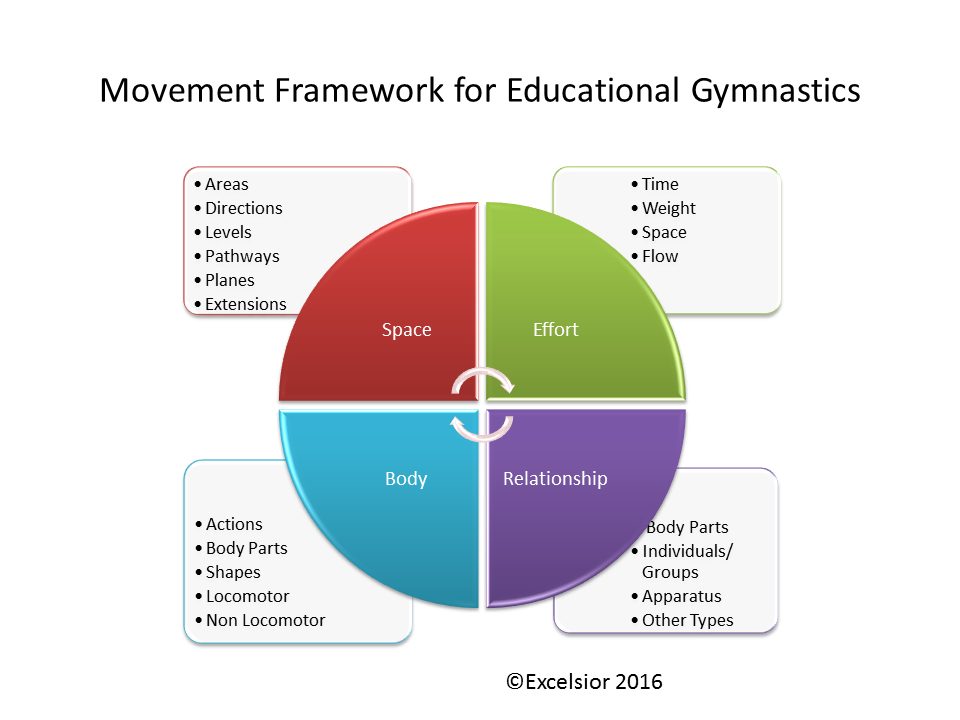

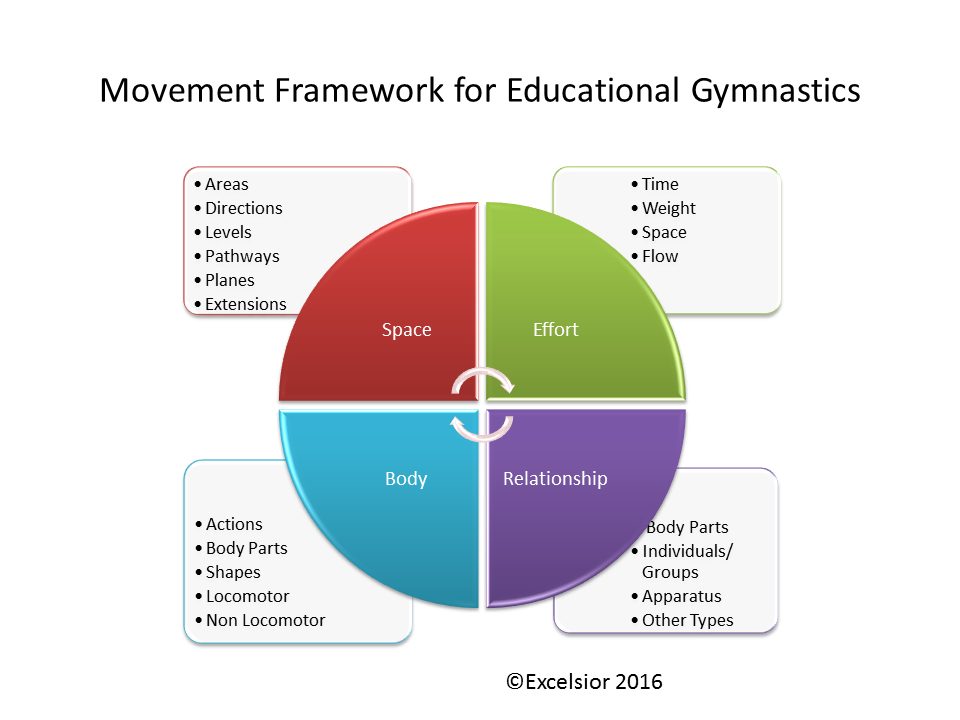

One way of removing personal bias and inertia is to use a movement framework to tweak the existing exercises. Rudolf Laban developed this in the 1950s for dance and physical education specialists. Subsequently adopted it in the UK in the 1960s and the USA in the 1970s. This article shall outline the framework and how it can be used by every sports coach with skipping as a specific example.

Overview

Rather than constantly trying to learn and describe new exercises and dance moves, Laban designed a system that described movement. This could then be interpreted differently by different subjects if the instructions were general enough. This allows for exploration by the athletes. It is less good for giving specific technical instruction to achieve a quick fix: but coaches already have that in their coaching toolbox.

The Framework

The four main aspects of movement are divided into four areas:

- Space

- Body

- Effort

- Relationship

Each of these four areas is then sub-divided further that help to refine the tasks.

For example, in space, pathways are familiar to football coaches. They just call it something different: streaks (linear), flares (curved), and post (zig-zag) routes. Usually, the routes are very specific and confined and take time to perfect. But teaching these specific footwork patterns is a lot easier if the athletes have a very broad base of movement skills upon which they can build.

Under the effort, weight does not refer to an athlete’s mass but the heaviness or lightness of their movement. The coach might describe running as ‘lightly across the grass so that you don’t damage a single blade’: this would encourage faster leg movements at top speed. Or, ‘push hard into the ground as if you were trying to move the earth’ at the start position in a sprint race to allow more force to be expressed.

Explaining the whole framework is beyond the scope of this article, but the following two videos show highlight different ways it can be used.

Video 1. The athletes have to change the movement level and the type of movement every time they reach a cone. They get to choose within the framework. You can see how much they have to concentrate.

Video 2: In this one, the athletes mirror each other in a collaborative exercise. The pathway is straight, but the athletes can change the direction they face. They move from slow to fast (time, flow) and low to high (levels).

There are different solutions to both of these tasks. I can either set it up for them to discover or, as in the skipping example below, use the framework to help me plan.

How can we use this?

If we take skipping as an example, you might already do this as part of a warm-up. You get the athletes to skip forwards for a set distance, turn around, and then return. But if you use the movement framework, then you can add a huge amount of variety to this one exercise:

Space

Direction / Pathway / Levels. Skip forwards, skip backward, skip sideways in a straight line. The pathway remains the same, but the athletes face changes (sideways skipping is hard to coordinate). Change the pathway: instead of straight lines, do zig-zags, circles, round a box, a figure of 8, a spiral, or even try to draw an elephant with your pathway. Levels: normal skipping takes place on the medium level. The athletes will be moving in the upper level by trying to skip upwards or using the arms to reach up.

Body

Rather than the standard skip action, the arms and legs can do different things, that encourage and stimulate the athletes’ coordination. Arms: Can make symmetrical/asymmetrical shapes, forward, sideways, upwards and downwards. Legs: can be bent/ straight, front / back. For example, skipping with the right hand touching the left foot in front with a straight left leg and then the left hand touching the right foot behind with a bent right leg, skipping forwards, backward and sideways before changing the sides.

Effort

The athletes can do a rhythmical skip that is fast or slow. They can do an arrhythmical with a pause every 1-5 skips to show balance and control. They can operate in a confined space to work on spatial awareness or cover greater distances in a large space.

Relationships

They can work in pairs collaboratively, shoulder-to-shoulder to match their partners’ timing, or work competitively in a shadow evasion game where they try to change direction and lose their partner while skipping. They can go around obstacles or over different surfaces to improve their ground contact time.

Combinations

You can combine the different movements once the athletes are familiar and competent with the different types of skipping (be patient, this is harder than it sounds). For example, they can change both direction and pathway while doing asymmetrical arm actions. The skipping can be combined with other movements using the framework. You can skip forwards, side shuffle sideways, run backward on a straight pathway where your direction changes, or keep your direction facing forwards and do the same actions where the pathway goes around three sides of a square.

Conclusion

This was a brief introduction. But Imagine warm-ups where athletes were taken through different combinations of movement that included skipping, crawling, and running at different speeds, directions, levels and pathways. The athletes would constantly have to think and concentrate on what they were doing rather than going into auto-pilot. When the coach came to teach specific skills, such as the wide receiver routes, the athletes would be physically and mentally ready.

Over the longer term, young athletes can develop their movement competency and rarely get bored. Nor will the coach.

RECOMMENDED FOR YOU

MOST POPULAR

Applying Movement Framework For Athletes

It is easy to get stuck in a rut as a coach. We get comfortable with a series of exercises in our warm-ups and drills and repeat them for years on end. Occasionally we see an exercise that someone else has used, and we copy it. We tend to do what we are familiar and comfortable with and ignore those exercises that are unfamiliar or that we can’t do ourselves. If we limit what exercises we use with our athletes, we limit their potential.

One way of removing personal bias and inertia is to use a movement framework to tweak the existing exercises. Rudolf Laban developed this in the 1950s for dance and physical education specialists. Subsequently adopted it in the UK in the 1960s and the USA in the 1970s. This article shall outline the framework and how it can be used by every sports coach with skipping as a specific example.

Overview

Rather than constantly trying to learn and describe new exercises and dance moves, Laban designed a system that described movement. This could then be interpreted differently by different subjects if the instructions were general enough. This allows for exploration by the athletes. It is less good for giving specific technical instruction to achieve a quick fix: but coaches already have that in their coaching toolbox.

The Framework

The four main aspects of movement are divided into four areas:

- Space

- Body

- Effort

- Relationship

Each of these four areas is then sub-divided further that help to refine the tasks.

For example, in space, pathways are familiar to football coaches. They just call it something different: streaks (linear), flares (curved), and post (zig-zag) routes. Usually, the routes are very specific and confined and take time to perfect. But teaching these specific footwork patterns is a lot easier if the athletes have a very broad base of movement skills upon which they can build.

Under the effort, weight does not refer to an athlete’s mass but the heaviness or lightness of their movement. The coach might describe running as ‘lightly across the grass so that you don’t damage a single blade’: this would encourage faster leg movements at top speed. Or, ‘push hard into the ground as if you were trying to move the earth’ at the start position in a sprint race to allow more force to be expressed.

Explaining the whole framework is beyond the scope of this article, but the following two videos show highlight different ways it can be used.

Video 1. The athletes have to change the movement level and the type of movement every time they reach a cone. They get to choose within the framework. You can see how much they have to concentrate.

Video 2: In this one, the athletes mirror each other in a collaborative exercise. The pathway is straight, but the athletes can change the direction they face. They move from slow to fast (time, flow) and low to high (levels).

There are different solutions to both of these tasks. I can either set it up for them to discover or, as in the skipping example below, use the framework to help me plan.

How can we use this?

If we take skipping as an example, you might already do this as part of a warm-up. You get the athletes to skip forwards for a set distance, turn around, and then return. But if you use the movement framework, then you can add a huge amount of variety to this one exercise:

Space

Direction / Pathway / Levels. Skip forwards, skip backward, skip sideways in a straight line. The pathway remains the same, but the athletes face changes (sideways skipping is hard to coordinate). Change the pathway: instead of straight lines, do zig-zags, circles, round a box, a figure of 8, a spiral, or even try to draw an elephant with your pathway. Levels: normal skipping takes place on the medium level. The athletes will be moving in the upper level by trying to skip upwards or using the arms to reach up.

Body

Rather than the standard skip action, the arms and legs can do different things, that encourage and stimulate the athletes’ coordination. Arms: Can make symmetrical/asymmetrical shapes, forward, sideways, upwards and downwards. Legs: can be bent/ straight, front / back. For example, skipping with the right hand touching the left foot in front with a straight left leg and then the left hand touching the right foot behind with a bent right leg, skipping forwards, backward and sideways before changing the sides.

Effort

The athletes can do a rhythmical skip that is fast or slow. They can do an arrhythmical with a pause every 1-5 skips to show balance and control. They can operate in a confined space to work on spatial awareness or cover greater distances in a large space.

Relationships

They can work in pairs collaboratively, shoulder-to-shoulder to match their partners’ timing, or work competitively in a shadow evasion game where they try to change direction and lose their partner while skipping. They can go around obstacles or over different surfaces to improve their ground contact time.

Combinations

You can combine the different movements once the athletes are familiar and competent with the different types of skipping (be patient, this is harder than it sounds). For example, they can change both direction and pathway while doing asymmetrical arm actions. The skipping can be combined with other movements using the framework. You can skip forwards, side shuffle sideways, run backward on a straight pathway where your direction changes, or keep your direction facing forwards and do the same actions where the pathway goes around three sides of a square.

Conclusion

This was a brief introduction. But Imagine warm-ups where athletes were taken through different combinations of movement that included skipping, crawling, and running at different speeds, directions, levels and pathways. The athletes would constantly have to think and concentrate on what they were doing rather than going into auto-pilot. When the coach came to teach specific skills, such as the wide receiver routes, the athletes would be physically and mentally ready.

Over the longer term, young athletes can develop their movement competency and rarely get bored. Nor will the coach.