The Importance of Triphasic Training, Part 4: The Concentric Phase

The concentric phase of the triphasic training model is the sexy part of dynamic muscle action. It’s the rock star that gets all the attention. You never walk into a gym and ask someone, “How much can you eccentrically lower to your chest?” You walk up and ask, “How much do you Bench?” You’re asking how much weight they can concentrically lift by pushing it off their chest.

The concentric phase is the measuring stick used to evaluate all athletic performance. How much can you lift? How far can you jump? How fast can you run? These are all performance measures based on force output measured in the concentric phase. Specifically as it relates to dynamic movement, the concentric phase is the measure of an athlete’s rate of force development (RFD).

In any dynamic movement, the combined force of the stretch reflex and stretch-shortening cycle aids the RFD. Recall from Part 2 and Part 3 of this series that the amount of potential energy stored within the musculoskeletal structure depends on the preceding eccentric and isometric contractions. When we understand how the concentric phase works in conjunction with these phases, we see why the concentric phase is imperative for maximizing explosive strength, RFD and performance. Would Nolan Ryan have been as intimidating without his fastball? Would Walter Payton have been as great if he couldn’t cut? The answer: an emphatic “No!” An athlete who can quickly build and absorb energy is ineffective if he cannot use that energy concentrically to rapidly produce force.

The true importance of training the concentric phase is the synchronization of the entire triphasic muscle action—maximizing the energy transfer from the preceding eccentric and isometric phases into a unified, explosive and dynamic movement. For the purpose of simplicity, we are going to package these mechanisms into two categories—inhibition/disinhibition and synchronization.

Inhibition/Disinhibition

In every muscular action, there is an agonist and an antagonist, an inhibitor and a disinhibitor. For our purposes here, all you need to understand is that while the agonist is concentrically contracting (shortening) to produce force, the antagonist is eccentrically contracting (lengthening). The purpose of the eccentric contraction is to try to decelerate the speed and force of the concentric contraction to protect the joints and ensure that the antagonist muscle doesn’t tear from rapid stretching. Training the concentric phase to perform explosive dynamic movements improves intermuscular coordination, allowing for the inhibition of the antagonist muscle and resulting in maximal RFD. Put another way, by training the concentric phase, you’re also training the inhibition of the antagonist.

Synchronization

There’s no question that an athlete who can generate more explosive force in less time has a decisive advantage. However, the advantage only goes to athletes who can unleash that power in a manner that gives them a performance edge. Nolan Ryan could touch 100 mph on the radar gun consistently, but that’s not what made him a Hall of Fame pitcher. The ability to place those 100 mph fastballs wherever the catcher put his glove is what made him Ryan the most feared pitcher of his era.

As an example, compare the Hang Clean to a Romanian Deadlift and Shrug. A novice athlete can quickly learn to perform a proper Romanian Deadlift and Shrug. It is a slow, controlled movement that allows time for the athlete’s neuromuscular system to interpret, process and execute the movement. On the other hand, teaching the Hang Clean can be a long and arduous process, even though it’s similar to the RDL and Shrug. In the case of the Hang Clean, decreasing the weight and increasing the speed of the exercise overloads the athlete’s neuromuscular system.

The point is that like the eccentric and isometric phases of a dynamic movement, the concentric phase is a learned and trainable skill. An athlete can learn to concentrically perform a Back Squat in a few minutes. It’s intuitive since it’s a neuromuscular action that is performed on a daily basis. However, teaching an athlete to move a bar like a shot out of a cannon takes time and a great deal of concentric-focused training.

How to Apply Concentric Training

This is fairly simple and straightforward—train fast! Concentric training will look very familiar to most, because it’s the predominant form of stress used in training. However, it only looks similar on paper. An athlete training concentrically after first building a solid foundation of eccentric and isometric strength will be able to move loads at much higher velocities.

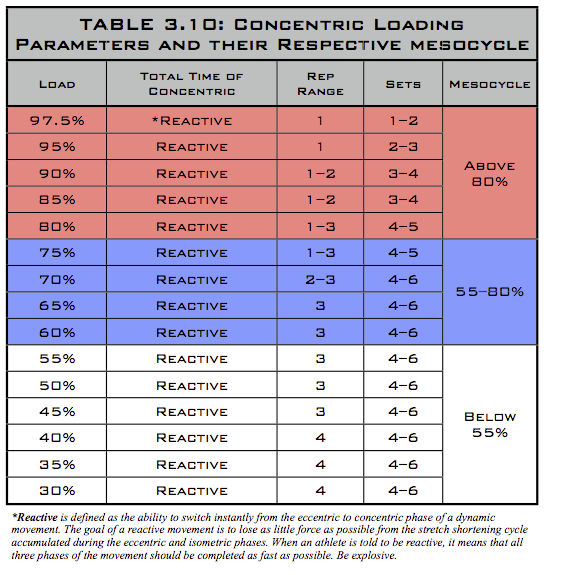

Table 3.10 is a breakdown of the loading parameters for an athletic model of training. Remember, athletes aren’t bodybuilders. The percentages and reps correlate to ensure that each rep is high-quality, neurological work aimed at producing high levels of force. In addition, the loading variables are designated by color, showing the parameters for each mesocycle:

The most important thing to remember when performing dynamic, concentric-focused work is to push against the bar as hard as possible, driving it all the way through its entire range of motion. Again, the focus should always be on developing a synchronized, powerful concentric contraction.

Concentric Exercise Videos

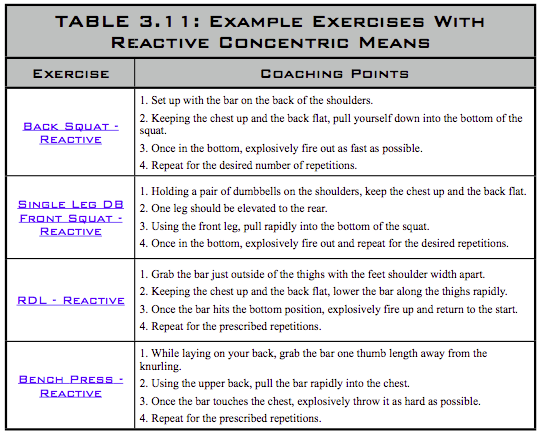

Back Squat

Single-Leg Dumbbell Front Squat

RDL

Bench Press

For more about Triphasic Training, check out Triphasic Training: A systematic approach to elite speed and explosive strength performance. You can also find great training advice and tips from the elite athletes and coaches who use it on Facebook and Twitter (@TriphasicTrain).

RECOMMENDED FOR YOU

MOST POPULAR

The Importance of Triphasic Training, Part 4: The Concentric Phase

The concentric phase of the triphasic training model is the sexy part of dynamic muscle action. It’s the rock star that gets all the attention. You never walk into a gym and ask someone, “How much can you eccentrically lower to your chest?” You walk up and ask, “How much do you Bench?” You’re asking how much weight they can concentrically lift by pushing it off their chest.

The concentric phase is the measuring stick used to evaluate all athletic performance. How much can you lift? How far can you jump? How fast can you run? These are all performance measures based on force output measured in the concentric phase. Specifically as it relates to dynamic movement, the concentric phase is the measure of an athlete’s rate of force development (RFD).

In any dynamic movement, the combined force of the stretch reflex and stretch-shortening cycle aids the RFD. Recall from Part 2 and Part 3 of this series that the amount of potential energy stored within the musculoskeletal structure depends on the preceding eccentric and isometric contractions. When we understand how the concentric phase works in conjunction with these phases, we see why the concentric phase is imperative for maximizing explosive strength, RFD and performance. Would Nolan Ryan have been as intimidating without his fastball? Would Walter Payton have been as great if he couldn’t cut? The answer: an emphatic “No!” An athlete who can quickly build and absorb energy is ineffective if he cannot use that energy concentrically to rapidly produce force.

The true importance of training the concentric phase is the synchronization of the entire triphasic muscle action—maximizing the energy transfer from the preceding eccentric and isometric phases into a unified, explosive and dynamic movement. For the purpose of simplicity, we are going to package these mechanisms into two categories—inhibition/disinhibition and synchronization.

Inhibition/Disinhibition

In every muscular action, there is an agonist and an antagonist, an inhibitor and a disinhibitor. For our purposes here, all you need to understand is that while the agonist is concentrically contracting (shortening) to produce force, the antagonist is eccentrically contracting (lengthening). The purpose of the eccentric contraction is to try to decelerate the speed and force of the concentric contraction to protect the joints and ensure that the antagonist muscle doesn’t tear from rapid stretching. Training the concentric phase to perform explosive dynamic movements improves intermuscular coordination, allowing for the inhibition of the antagonist muscle and resulting in maximal RFD. Put another way, by training the concentric phase, you’re also training the inhibition of the antagonist.

Synchronization

There’s no question that an athlete who can generate more explosive force in less time has a decisive advantage. However, the advantage only goes to athletes who can unleash that power in a manner that gives them a performance edge. Nolan Ryan could touch 100 mph on the radar gun consistently, but that’s not what made him a Hall of Fame pitcher. The ability to place those 100 mph fastballs wherever the catcher put his glove is what made him Ryan the most feared pitcher of his era.

As an example, compare the Hang Clean to a Romanian Deadlift and Shrug. A novice athlete can quickly learn to perform a proper Romanian Deadlift and Shrug. It is a slow, controlled movement that allows time for the athlete’s neuromuscular system to interpret, process and execute the movement. On the other hand, teaching the Hang Clean can be a long and arduous process, even though it’s similar to the RDL and Shrug. In the case of the Hang Clean, decreasing the weight and increasing the speed of the exercise overloads the athlete’s neuromuscular system.

The point is that like the eccentric and isometric phases of a dynamic movement, the concentric phase is a learned and trainable skill. An athlete can learn to concentrically perform a Back Squat in a few minutes. It’s intuitive since it’s a neuromuscular action that is performed on a daily basis. However, teaching an athlete to move a bar like a shot out of a cannon takes time and a great deal of concentric-focused training.

How to Apply Concentric Training

This is fairly simple and straightforward—train fast! Concentric training will look very familiar to most, because it’s the predominant form of stress used in training. However, it only looks similar on paper. An athlete training concentrically after first building a solid foundation of eccentric and isometric strength will be able to move loads at much higher velocities.

Table 3.10 is a breakdown of the loading parameters for an athletic model of training. Remember, athletes aren’t bodybuilders. The percentages and reps correlate to ensure that each rep is high-quality, neurological work aimed at producing high levels of force. In addition, the loading variables are designated by color, showing the parameters for each mesocycle:

The most important thing to remember when performing dynamic, concentric-focused work is to push against the bar as hard as possible, driving it all the way through its entire range of motion. Again, the focus should always be on developing a synchronized, powerful concentric contraction.

Concentric Exercise Videos

Back Squat

Single-Leg Dumbbell Front Squat

RDL

Bench Press

For more about Triphasic Training, check out Triphasic Training: A systematic approach to elite speed and explosive strength performance. You can also find great training advice and tips from the elite athletes and coaches who use it on Facebook and Twitter (@TriphasicTrain).