How to Train for Firefighter Academy

Firefighters are critical to the safety and well-being of our society. Without them, we would be in great danger daily which makes it a critical yet difficult occupation. The mental and physical demands can be quite strenuous; thus, one must be prepared to handle anything that the job brings. If one is seeking to become a firefighter, one must pass physical tests and successfully complete the fire academy. Preparing for fire academy and being a successful firefighter thereafter requires a deep understanding of both what the job demands, and how to physically prepare for it.

Physical and Biomechanical Demands of Firefighting

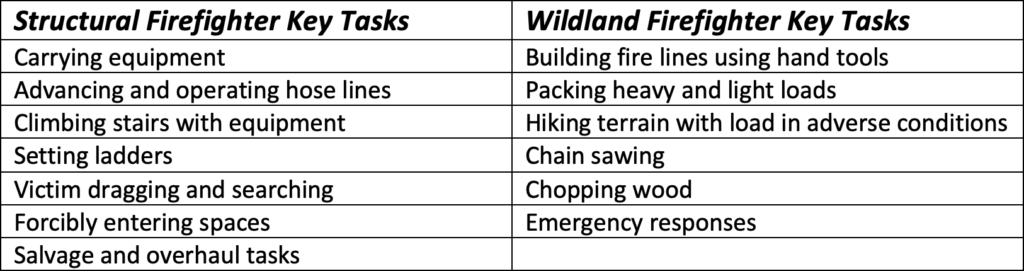

Before diving into exactly how one should prepare for a fire academy, it’s critical to understand what the job entails and what setting one will be working in. Critical tasks vary between structural and wildland firefighters including the following:

From a biomechanical perspective, firefighters perform most of their movements in the sagittal and transverse planes, which is important to remember when selecting exercises for a strength training program later. They use nearly every joint in their body while engaging major muscle groups of both the upper and lower body through dynamic and isometric muscle contractions depending on the task at hand. As such, firefighters need to possess adequate strength, power, and endurance in both their upper and lower bodies to successfully perform the tasks at hand.

Strengthening the body not only helps a firefighter perform their job more successfully, but it can also help mitigate the risk of injury. Some of the most common injuries that occur for firefighters include:

– Sprains, strains, and muscle pain (particularly from pulling, or lifting equipment)

– Slips, trips, falls, or contact with an object that strikes them

– Tripping over an object.

Muscle imbalances play a major factor in the occurrence of injuries as well, therefore it’s key to not only develop strength but also correct any asymmetries or weaknesses one may possess. According to the National Strength and Conditioning Association (NSCA), the most commonly injured body part of a firefighter is their legs, followed by the feet, arms, hands, trunk, shoulders, and neck in that order.

Possessing strength and a body that moves well is only part of the equation to being physically prepared as a firefighter, the other major component is aerobic and anaerobic fitness. Most tasks in firefighting are of moderate to high intensity. Cardiorespiratory demands of structural firefighting result in oxygen uptake levels that are 63%-97% of maximum and heart rate values between 84% and 100% of maximum according to the NSCA. Not only do the high-intensity activities elevate the two components while performing them, but they also can remain elevated for up to 30 minutes afterward, consistent with the post-exercise oxygen consumption effect induced by high-intensity training methods.

According to the NSCA, the minimum suggested aerobic capacity for being able to perform structural foreground rescue tasks is 42ml -kg-1/min-1 or 12 METS. The peak blood lactate values a firefighter has during similar tasks can range between 6-13mmol/L which is a high level of anaerobic stress and must be trained to sustain output for both performance and safety. To summarize, the aerobic and anaerobic fitness levels of firefighters must be higher than general population standards and be able to be sustained for long periods.

Preparing for the academy and the CPAT

To successfully become a firefighter, one must pass the candidate physical ability test (CPAT). The CPAT test is the recognized standard for measuring an individual’s ability to handle the physical demands of being a firefighter. One must perform 8 tasks successfully in under 10 minutes and 20 seconds to pass which include the following:

o 75lb weighted stair climb

o Hose Drag

o Equipment Carry

o Ladder Raise and extension

o Forcible entry using 10lb sledgehammer

o Search portion that involves crawling at least 70 feet

o Rescue portion which involves dragging a 165lb mannequin

o Ceiling breach and pull.

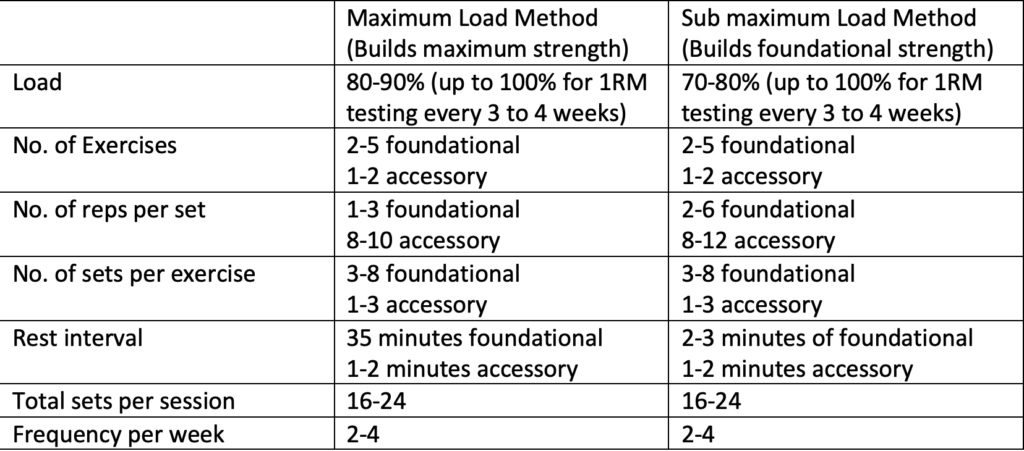

As discussed earlier, each of the tasks requires a different physiological and biomechanical component to be successful. A well-thought-out and effective strength and conditioning program can do just that if executed correctly. There is, however, no one size fit’s all program but instead some general guidelines one can follow to build the strength required for a solid foundation of fitness. The table below gives general guidelines for building strength.

Adapted from Tudor Bompa

Some key movements to include in the program as a firefighter include:

– Step-Ups

– Lunges

– Squats

– Rotational power movements (MB tosses, cable rotations, etc.)

– Anti-rotational movements (paloff presses, dead bugs, etc.)

This is by no means exhaustive; however, it is a great place to start and will provide the basis for developing general overall strength.

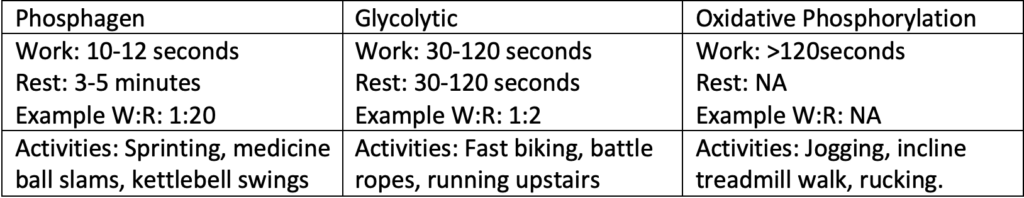

In terms of both aerobic and anaerobic conditioning, these must be addressed separately as well. Tasks such as the ladder raise tax the phosphagen system (~less than 10 seconds) whereas things like load carriage or victim rescue tax the glycolytic system (~30 seconds – 2 minutes), and activities such as hos operation or hiking with load lean towards oxidative phosphorylation (~ greater than 2 minutes). Essentially, a firefighter must adequately develop every energy system pathway effectively, hence why “going for a jog around the block” or hopping on the Stairmaster just won’t cut it. The “work to rest ratio, W: R” is what becomes critical when designing programs for energy system development as well as the modality of exercise. The table below provides rough outlines and examples of W: R rations as well as corresponding activities one can do to train them.

Outside of these two components, ensuring one has adequate mobility, stability, and movement capacity is of utmost importance. This ensures the safety and ability to perform all tasks a firefighter is confronted with. Seeking professional help with orthopedic issues is advised, however developing these components is an article for another day.

Summary:

To become a firefighter, one must pass a commonly administered test, the CPAT, which replicates the physical demands of the job. It is difficult both physically and mentally which requires tedious preparation to be successful. Strength, aerobic, and anaerobic fitness are all key pillars to succeed in the fire academy therefore they must be addressed with an effective strength and conditioning methods. Beyond fire academy, physical fitness assures that firefighters remain safe and can execute the job effectively.

RECOMMENDED FOR YOU

MOST POPULAR

How to Train for Firefighter Academy

Firefighters are critical to the safety and well-being of our society. Without them, we would be in great danger daily which makes it a critical yet difficult occupation. The mental and physical demands can be quite strenuous; thus, one must be prepared to handle anything that the job brings. If one is seeking to become a firefighter, one must pass physical tests and successfully complete the fire academy. Preparing for fire academy and being a successful firefighter thereafter requires a deep understanding of both what the job demands, and how to physically prepare for it.

Physical and Biomechanical Demands of Firefighting

Before diving into exactly how one should prepare for a fire academy, it’s critical to understand what the job entails and what setting one will be working in. Critical tasks vary between structural and wildland firefighters including the following:

From a biomechanical perspective, firefighters perform most of their movements in the sagittal and transverse planes, which is important to remember when selecting exercises for a strength training program later. They use nearly every joint in their body while engaging major muscle groups of both the upper and lower body through dynamic and isometric muscle contractions depending on the task at hand. As such, firefighters need to possess adequate strength, power, and endurance in both their upper and lower bodies to successfully perform the tasks at hand.

Strengthening the body not only helps a firefighter perform their job more successfully, but it can also help mitigate the risk of injury. Some of the most common injuries that occur for firefighters include:

– Sprains, strains, and muscle pain (particularly from pulling, or lifting equipment)

– Slips, trips, falls, or contact with an object that strikes them

– Tripping over an object.

Muscle imbalances play a major factor in the occurrence of injuries as well, therefore it’s key to not only develop strength but also correct any asymmetries or weaknesses one may possess. According to the National Strength and Conditioning Association (NSCA), the most commonly injured body part of a firefighter is their legs, followed by the feet, arms, hands, trunk, shoulders, and neck in that order.

Possessing strength and a body that moves well is only part of the equation to being physically prepared as a firefighter, the other major component is aerobic and anaerobic fitness. Most tasks in firefighting are of moderate to high intensity. Cardiorespiratory demands of structural firefighting result in oxygen uptake levels that are 63%-97% of maximum and heart rate values between 84% and 100% of maximum according to the NSCA. Not only do the high-intensity activities elevate the two components while performing them, but they also can remain elevated for up to 30 minutes afterward, consistent with the post-exercise oxygen consumption effect induced by high-intensity training methods.

According to the NSCA, the minimum suggested aerobic capacity for being able to perform structural foreground rescue tasks is 42ml -kg-1/min-1 or 12 METS. The peak blood lactate values a firefighter has during similar tasks can range between 6-13mmol/L which is a high level of anaerobic stress and must be trained to sustain output for both performance and safety. To summarize, the aerobic and anaerobic fitness levels of firefighters must be higher than general population standards and be able to be sustained for long periods.

Preparing for the academy and the CPAT

To successfully become a firefighter, one must pass the candidate physical ability test (CPAT). The CPAT test is the recognized standard for measuring an individual’s ability to handle the physical demands of being a firefighter. One must perform 8 tasks successfully in under 10 minutes and 20 seconds to pass which include the following:

o 75lb weighted stair climb

o Hose Drag

o Equipment Carry

o Ladder Raise and extension

o Forcible entry using 10lb sledgehammer

o Search portion that involves crawling at least 70 feet

o Rescue portion which involves dragging a 165lb mannequin

o Ceiling breach and pull.

As discussed earlier, each of the tasks requires a different physiological and biomechanical component to be successful. A well-thought-out and effective strength and conditioning program can do just that if executed correctly. There is, however, no one size fit’s all program but instead some general guidelines one can follow to build the strength required for a solid foundation of fitness. The table below gives general guidelines for building strength.

Adapted from Tudor Bompa

Some key movements to include in the program as a firefighter include:

– Step-Ups

– Lunges

– Squats

– Rotational power movements (MB tosses, cable rotations, etc.)

– Anti-rotational movements (paloff presses, dead bugs, etc.)

This is by no means exhaustive; however, it is a great place to start and will provide the basis for developing general overall strength.

In terms of both aerobic and anaerobic conditioning, these must be addressed separately as well. Tasks such as the ladder raise tax the phosphagen system (~less than 10 seconds) whereas things like load carriage or victim rescue tax the glycolytic system (~30 seconds – 2 minutes), and activities such as hos operation or hiking with load lean towards oxidative phosphorylation (~ greater than 2 minutes). Essentially, a firefighter must adequately develop every energy system pathway effectively, hence why “going for a jog around the block” or hopping on the Stairmaster just won’t cut it. The “work to rest ratio, W: R” is what becomes critical when designing programs for energy system development as well as the modality of exercise. The table below provides rough outlines and examples of W: R rations as well as corresponding activities one can do to train them.

Outside of these two components, ensuring one has adequate mobility, stability, and movement capacity is of utmost importance. This ensures the safety and ability to perform all tasks a firefighter is confronted with. Seeking professional help with orthopedic issues is advised, however developing these components is an article for another day.

Summary:

To become a firefighter, one must pass a commonly administered test, the CPAT, which replicates the physical demands of the job. It is difficult both physically and mentally which requires tedious preparation to be successful. Strength, aerobic, and anaerobic fitness are all key pillars to succeed in the fire academy therefore they must be addressed with an effective strength and conditioning methods. Beyond fire academy, physical fitness assures that firefighters remain safe and can execute the job effectively.