Off-Season Conditioning for Football: Metabolic Running

Football players have two important time periods to work on conditioning—at the start of the off-season and the two to three weeks leading up to two-a-days. Developing a good conditioning base during these periods is critical to maximizing gains from your summer training program and preparing for the season.

Think of it like building the base of a pyramid. The larger the base, the higher the pyramid can be built. Who will get stronger, an athlete who can handle 10 sets of two reps at 90 percent of his one-rep max, or one who can only do six sets at the same intensity? The better-conditioned athlete will go into the strength, power and speed phases of his off-season program with the ability to handle more work and perform more quality reps.

The bottom line: a high level of conditioning gives you the ability to handle high-stress workouts. High-stress workouts mean greater adaptation. Greater adaptation means better strength, speed and explosive power.

So, how do you develop a broad base of conditioning in only two to four weeks of training? Try running. Most athletes run 100 yards in some format, whether in a straight sprint or a shuttle. Regardless, running 100 yards over and over again seems to be the gold standard of conditioning for football. However, except for those rare end zone to end zone kickoff returns, you will never run 100 yards straight in a game. That means that the standard method for football conditioning has no specific transfer to how the vast majority of the game is played.

But this is only half of the problem. Football is played with 360 degrees of movement. For example, most of the time, defensive players don’t even run forward. They move laterally to flow with a play or backwards to drop into coverage. It only makes sense that a conditioning program should incorporate game-time movements so they can transfer easily to the field.

Let’s look at the actual muscular systems recruited when running. In conventional, straight-ahead running, you primarily work the large muscles of your lower limbs—the quads, hamstrings, glutes, iliacus and psoas. Fine and dandy. But what about the other muscles—the small, support muscles most people forget about, which are used to help rotate the hips, allowing fluid movement for planting, cutting, crossing over, opening up and shuffling?

No matter how much a player runs and conditions during the off-season, he will most likely have sore legs during the first week of practice. Specifically, the inside of his thighs and groin will be sore. That’s because those muscles are not trained by conventional, straight-ahead running.

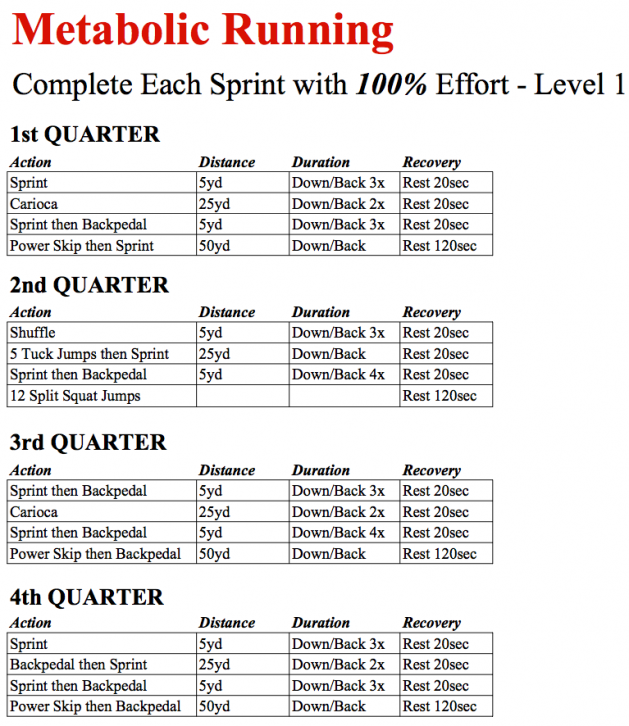

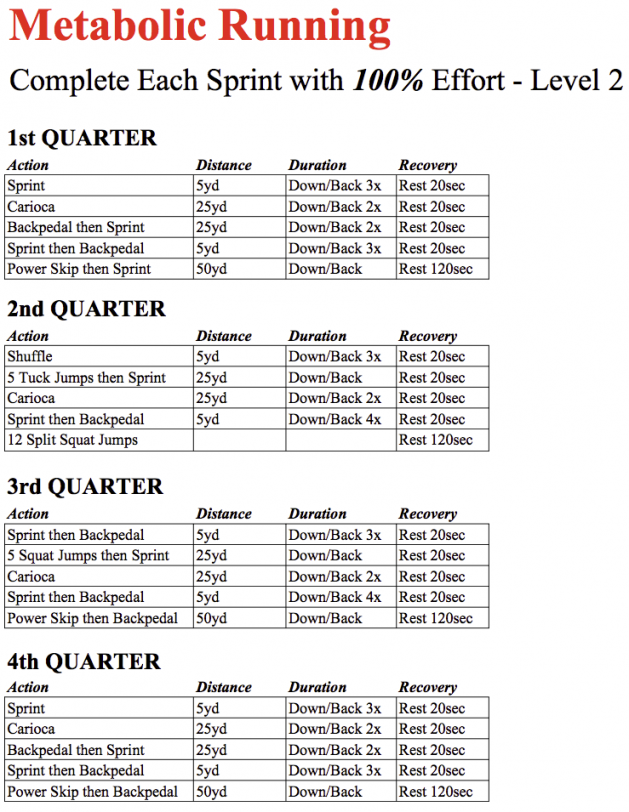

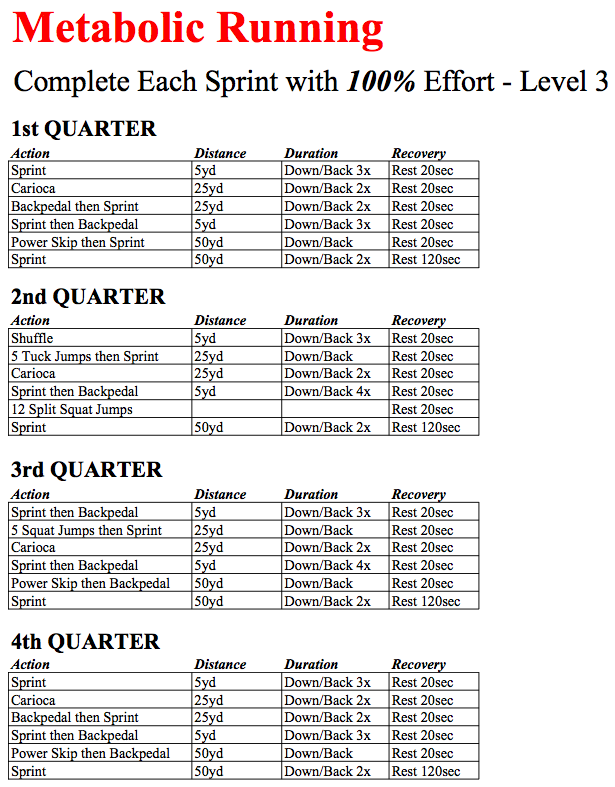

Now that you understand the basics of conditioning for football, it’s time to get to the program. Metabolic running is simple but effective. You run sprints—like in a normal conditioning program—but each sprint is a different distance and performed with a different movement pattern, such as shuffle, Carioca, skip, etc. This ensures the development of all the muscles in your legs and hips.

There are three keys to metabolic running:

- Every sprint is performed with 100 percent intensity. No exceptions! You might be doing a Carioca, but you must do it as fast as you possibly can.

- Follow the rest intervals religiously. Don’t take longer than 20 seconds between sprints and two minutes between quarters.

- Get a training partner. Get a training partner and race every sprint. My pro guys do this every summer, and the guy who wins the fewest number of sprints buys lunch for everyone else. Until you try racing a partner, you can’t understand how physically taxing it is. It will make you want to quit—but don’t.

Replace your conventional conditioning program with metabolic running twice a week for three or four weeks, and you will feel the difference during the first week of two-a-days. Start with Level 1 and progress to Level 3. (Warning: Level 3 is not for the faint of heart. Possible side effects: pain, vomiting, cursing my name and crying for your momma.)

Customize your off-season football workout at the STACK Performance Center.

For more great training tips, check out Triphasic Training: A systematic approach to elite speed and explosive strength performance.

Ben Peterson, author of Triphasic Training, is currently pursuing his doctorate in kinesiology and exercise physiology at the University of Minnesota. A graduate of Northwestern University, Peterson started his career in 2008, working for the Minnesota Twins as an assistant strength and conditioning coach. Over the past four years, he has worked with hundreds of professional athletes in the NFL, NHL and MLB. Most recently, he has served as a consultant for Octagon Hockey, spending the NHL off-season working with their athletes in the Minneapolis area.

RECOMMENDED FOR YOU

MOST POPULAR

Off-Season Conditioning for Football: Metabolic Running

Football players have two important time periods to work on conditioning—at the start of the off-season and the two to three weeks leading up to two-a-days. Developing a good conditioning base during these periods is critical to maximizing gains from your summer training program and preparing for the season.

Think of it like building the base of a pyramid. The larger the base, the higher the pyramid can be built. Who will get stronger, an athlete who can handle 10 sets of two reps at 90 percent of his one-rep max, or one who can only do six sets at the same intensity? The better-conditioned athlete will go into the strength, power and speed phases of his off-season program with the ability to handle more work and perform more quality reps.

The bottom line: a high level of conditioning gives you the ability to handle high-stress workouts. High-stress workouts mean greater adaptation. Greater adaptation means better strength, speed and explosive power.

So, how do you develop a broad base of conditioning in only two to four weeks of training? Try running. Most athletes run 100 yards in some format, whether in a straight sprint or a shuttle. Regardless, running 100 yards over and over again seems to be the gold standard of conditioning for football. However, except for those rare end zone to end zone kickoff returns, you will never run 100 yards straight in a game. That means that the standard method for football conditioning has no specific transfer to how the vast majority of the game is played.

But this is only half of the problem. Football is played with 360 degrees of movement. For example, most of the time, defensive players don’t even run forward. They move laterally to flow with a play or backwards to drop into coverage. It only makes sense that a conditioning program should incorporate game-time movements so they can transfer easily to the field.

Let’s look at the actual muscular systems recruited when running. In conventional, straight-ahead running, you primarily work the large muscles of your lower limbs—the quads, hamstrings, glutes, iliacus and psoas. Fine and dandy. But what about the other muscles—the small, support muscles most people forget about, which are used to help rotate the hips, allowing fluid movement for planting, cutting, crossing over, opening up and shuffling?

No matter how much a player runs and conditions during the off-season, he will most likely have sore legs during the first week of practice. Specifically, the inside of his thighs and groin will be sore. That’s because those muscles are not trained by conventional, straight-ahead running.

Now that you understand the basics of conditioning for football, it’s time to get to the program. Metabolic running is simple but effective. You run sprints—like in a normal conditioning program—but each sprint is a different distance and performed with a different movement pattern, such as shuffle, Carioca, skip, etc. This ensures the development of all the muscles in your legs and hips.

There are three keys to metabolic running:

- Every sprint is performed with 100 percent intensity. No exceptions! You might be doing a Carioca, but you must do it as fast as you possibly can.

- Follow the rest intervals religiously. Don’t take longer than 20 seconds between sprints and two minutes between quarters.

- Get a training partner. Get a training partner and race every sprint. My pro guys do this every summer, and the guy who wins the fewest number of sprints buys lunch for everyone else. Until you try racing a partner, you can’t understand how physically taxing it is. It will make you want to quit—but don’t.

Replace your conventional conditioning program with metabolic running twice a week for three or four weeks, and you will feel the difference during the first week of two-a-days. Start with Level 1 and progress to Level 3. (Warning: Level 3 is not for the faint of heart. Possible side effects: pain, vomiting, cursing my name and crying for your momma.)

Customize your off-season football workout at the STACK Performance Center.

For more great training tips, check out Triphasic Training: A systematic approach to elite speed and explosive strength performance.

Ben Peterson, author of Triphasic Training, is currently pursuing his doctorate in kinesiology and exercise physiology at the University of Minnesota. A graduate of Northwestern University, Peterson started his career in 2008, working for the Minnesota Twins as an assistant strength and conditioning coach. Over the past four years, he has worked with hundreds of professional athletes in the NFL, NHL and MLB. Most recently, he has served as a consultant for Octagon Hockey, spending the NHL off-season working with their athletes in the Minneapolis area.