You could say that a runner’s bodyweight should abide by the Goldilocks principle. You don’t want to be too heavy, of course. But you also don’t want to be too light. Somewhere in the middle is juuuust right.

Matt Fitzgerald, sports nutritionist and best-selling author of Racing Weight: How to Get Lean for Peak Performance, says every runner has what an MD would describe as a healthy range when it comes to their body weight. “Doctors can define this range taking into consideration variables like age, gender and height,” Fitzgerald says.

A runner toeing the starting line of race with eyes set on a PR does not want to be under that weight range, and certainly not over it, because in either case, his or her performance will suffer.

“The ideal racing weight is close to the bottom of your healthy weight range,” Fitzgerald explains. “It’s just a little bit above the minimum required by good health to be ready to perform at your best.”

To runners wanting to benefit from this principle, Fitzgerald offers two critical diet rules.

Running Diet Rule #1: Chart Your Performances Against the Scale

“The only way to determine your best race weight is to attain it,” Fitzgerald says, and he offers the example of 2:07 American marathoner Dathan Ritzenhein, who always charts his performances against readings on the scale. “He knows that when he’s at 130 pounds, that’s too heavy for him to race at his best. He also knows that when he’s at 120 pounds, it’s too low; his performance will suffer,” according to Fitzgerald. What Ritzenhein has learned over the course of his career is that to unleash an optimal race performance, he should tip the scale at 125 pounds.

Running Diet Rule #2: Ditch Junk Food in Favor of High-Quality Eats

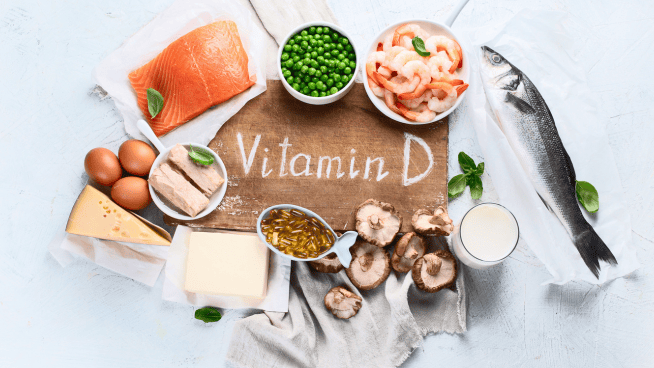

“Food quality is the single most important feature of an athlete’s diet,” Fitzgerald says. How do you determine if a food is high quality? It’s not complicated, according to Fitzgerald. “Everything you need to know about how to pick healthy foods, you learned in the third grade. Lean meats, fish, vegetables, fruits, nuts, seeds are all high-quality foods. Diet soda, donuts, pizza: all low-quality junk food.

Fitzgerald emphasizes that cleaning your diet is not about eating less food, but choosing better foods. “Restricting quantity to lose weight might work fine for non-athletes, but for athletes it’s a dangerous way to think. You can’t perform at an unhealthy low weight. In two weeks, you’ll be cooked.”

Patterns of food restriction that drop an athlete below the healthy weight range are synonymous with eating disorders. “Being lean for performance is not about being as lean as you can possibly get. It’s about being close to the bottom of the healthy range of weight.”

This relatively simple approach to a high-performance diet may be uncomplicated, Fitzgerald says, but it works. In Racing Weight, he reports on the food logs of 18 elite endurance athletes, only one of whom follows a diet with a name, that being ultrarunning great Scott Jurek, well-known as a vegan. The rest are what Fitzgerald refers to as diet-agnostic. They don’t follow a prescription with a brand name—like the Atkins diet, for example. The best runners follow a much more basic, practical approach.

American runner Chris Solinsky is a great example, according to Fitzgerald. Despite being unusually tall for a champion runner (he’s 6-foot-1), Solinsky piled up eight state titles in high school and five NCAA Division I titles at the University of Wisconsin. BUt after he graduated and became a professional runner, he failed to make the 2008 Olympic team.

According to Fitzgerald, Solinsky, who raced at 165 pounds during his days as a Badger, took an honest look at his diet. “It wasn’t that great,” Fitzgerald says. “He never cooked. Frozen pizza was a staple. If he had been a 125-pound runner, he might never have been concerned about his diet. But he was 165 pounds, so it was something to think about.”

But after falling just short of making the 2008 Olympic team, Solinsky decided to straighten up his nutrition. “It was intuitive sort of stuff,” Fitzgerald says. “He got rid of the frozen pizzas and made simple substitutions.”

Solinsky’s weight sizzled down to 156 pounds. On May 10, 2010, he ran his first 10,000-meter race on the track at the Stanford Invitational, recording a 26:59.60, breaking the American record, and making him the first non-African to go under the 27-minute barrier. A month later he cracked 13 minutes in a 5000-meter race.

Fitzgerald says that Solinsky’s path illustrates how simple the approach can be. “The body is intelligent. It’s a form-follows-function sort of thing.” If you feed your body the right foods and nutrients and train hard, it will respond by shedding excess body fat while preserving the right amount of muscle mass, bone density and hydration levels.

Matt Fitzgerald’s forthcoming Racing Weight Cookbook is scheduled for release in January 2014, along with an online calculator to help you dial in the right number. Get more info at www.racingweight.com.

RECOMMENDED FOR YOU

You could say that a runner’s bodyweight should abide by the Goldilocks principle. You don’t want to be too heavy, of course. But you also don’t want to be too light. Somewhere in the middle is juuuust right.

Matt Fitzgerald, sports nutritionist and best-selling author of Racing Weight: How to Get Lean for Peak Performance, says every runner has what an MD would describe as a healthy range when it comes to their body weight. “Doctors can define this range taking into consideration variables like age, gender and height,” Fitzgerald says.

A runner toeing the starting line of race with eyes set on a PR does not want to be under that weight range, and certainly not over it, because in either case, his or her performance will suffer.

“The ideal racing weight is close to the bottom of your healthy weight range,” Fitzgerald explains. “It’s just a little bit above the minimum required by good health to be ready to perform at your best.”

To runners wanting to benefit from this principle, Fitzgerald offers two critical diet rules.

Running Diet Rule #1: Chart Your Performances Against the Scale

“The only way to determine your best race weight is to attain it,” Fitzgerald says, and he offers the example of 2:07 American marathoner Dathan Ritzenhein, who always charts his performances against readings on the scale. “He knows that when he’s at 130 pounds, that’s too heavy for him to race at his best. He also knows that when he’s at 120 pounds, it’s too low; his performance will suffer,” according to Fitzgerald. What Ritzenhein has learned over the course of his career is that to unleash an optimal race performance, he should tip the scale at 125 pounds.

Running Diet Rule #2: Ditch Junk Food in Favor of High-Quality Eats

“Food quality is the single most important feature of an athlete’s diet,” Fitzgerald says. How do you determine if a food is high quality? It’s not complicated, according to Fitzgerald. “Everything you need to know about how to pick healthy foods, you learned in the third grade. Lean meats, fish, vegetables, fruits, nuts, seeds are all high-quality foods. Diet soda, donuts, pizza: all low-quality junk food.

Fitzgerald emphasizes that cleaning your diet is not about eating less food, but choosing better foods. “Restricting quantity to lose weight might work fine for non-athletes, but for athletes it’s a dangerous way to think. You can’t perform at an unhealthy low weight. In two weeks, you’ll be cooked.”

Patterns of food restriction that drop an athlete below the healthy weight range are synonymous with eating disorders. “Being lean for performance is not about being as lean as you can possibly get. It’s about being close to the bottom of the healthy range of weight.”

This relatively simple approach to a high-performance diet may be uncomplicated, Fitzgerald says, but it works. In Racing Weight, he reports on the food logs of 18 elite endurance athletes, only one of whom follows a diet with a name, that being ultrarunning great Scott Jurek, well-known as a vegan. The rest are what Fitzgerald refers to as diet-agnostic. They don’t follow a prescription with a brand name—like the Atkins diet, for example. The best runners follow a much more basic, practical approach.

American runner Chris Solinsky is a great example, according to Fitzgerald. Despite being unusually tall for a champion runner (he’s 6-foot-1), Solinsky piled up eight state titles in high school and five NCAA Division I titles at the University of Wisconsin. BUt after he graduated and became a professional runner, he failed to make the 2008 Olympic team.

According to Fitzgerald, Solinsky, who raced at 165 pounds during his days as a Badger, took an honest look at his diet. “It wasn’t that great,” Fitzgerald says. “He never cooked. Frozen pizza was a staple. If he had been a 125-pound runner, he might never have been concerned about his diet. But he was 165 pounds, so it was something to think about.”

But after falling just short of making the 2008 Olympic team, Solinsky decided to straighten up his nutrition. “It was intuitive sort of stuff,” Fitzgerald says. “He got rid of the frozen pizzas and made simple substitutions.”

Solinsky’s weight sizzled down to 156 pounds. On May 10, 2010, he ran his first 10,000-meter race on the track at the Stanford Invitational, recording a 26:59.60, breaking the American record, and making him the first non-African to go under the 27-minute barrier. A month later he cracked 13 minutes in a 5000-meter race.

Fitzgerald says that Solinsky’s path illustrates how simple the approach can be. “The body is intelligent. It’s a form-follows-function sort of thing.” If you feed your body the right foods and nutrients and train hard, it will respond by shedding excess body fat while preserving the right amount of muscle mass, bone density and hydration levels.

Matt Fitzgerald’s forthcoming Racing Weight Cookbook is scheduled for release in January 2014, along with an online calculator to help you dial in the right number. Get more info at www.racingweight.com.