The Top Speed Secret: Why Getting Faster Is the Ultimate Performance-Enhancer For Team Sport Athletes

Team sport athletes rarely reach max velocity during competition.

That’s just the reality. Fatigue becomes a factor shortly after the first whistle blows, and opportunities for the long, uninterrupted periods of linear sprinting needed to achieve max velocity rarely occur in the organic flow of a game.

So, in the name of being “sport-specific,” why even bother with max speed? Why not have team sport athletes get really good at running under fatigue, instead? That’s something we know will be unavoidable on game day, as the other team isn’t going to stop so you can “take a breather.” Mix in some short accelerations, which are much more common in competition for team sport athletes than long, max velocity sprints, and you’re good to go, right?

It sounds logical enough—which is exactly why this sort of thinking has been the default for team sport athletes for decades. Coaches say they want their players to get faster, but when it comes down to it, they’re really more worried about them being “out of shape.” That fear leads them to condition their athletes into oblivion.

Conditioning in the offseason. Conditioning before practice. Conditioning after practice. Conditioning during practice. Hustle to the next drill. Hustle to get water. Hustle back to the huddle. Hustle to get on the line for conditioning.

Many team sport athletes get lots and lots of exposure to fatigued sub-maximal running/training, yet very little exposure to max velocity. They get better at jogging while tired, but the high-volume takes a toll on their bodies.

What if instead of focusing on helping athletes maintain the likely mediocre speed they already possess, we shifted our perspective to making them truly faster? What if more speed was the ultimate trump card for outlasting an opponent?

Tony Holler, track coach at Plainfield North High School (Illinois) and inventor of the Feed the Cats methodology, is one man who’s shifting the paradigm when it comes to conditioning athletes.

“I’ve found conditioning to be the most over-used, over-valued, and counter-productive things in sport. In addition, it makes players slow,” Holler writes in a recent Track Football Consortium article on the topic.

“Conditioning is the act of intentionally getting athletes tired. And remember, ‘Any fool can get another fool tired.’”

Developing speed has long been a frustrating venture for many coaches. The main reasons for this, as Holler outlines in this STACK article, are athletes are made to run too far, too often and on too little rest to develop speed. Speed must also be a priority inside your program, not just something you wish for, and the simplest way to do that is by timing every sprint an athlete runs. When a number is attached to every effort, competition and intent skyrocket.

But an obsession with conditioning and “outworking” the opponent, which is especially prevalent in sports like football, often supersedes speed development. The norm becomes lots of work at 60-80% of max velocity, day after day. The body adapts to this implied demand, and players do get better at running gassers or 110s. But these adaptations do little for developing max speed (if anything, they tend to make you slower) and the constant high-volume work leaves players in a continuous state of exhaustion.

Most coaches view speed or conditioning as a one or the other proposition and, fearing the shame of having a “soft” team who didn’t work hard enough, consciously or subconsciously overvalue the latter.

But here’s the thing—enhancing your top speed is one of the best ways to enhance your conditioning, particularly for team sport athletes.

When your top speed increases, so does your speed reserve. Suddenly, what once represented 80% of your top speed might now represent 70%. Thus, the energy demands to achieve and maintain that speed are significantly reduced.

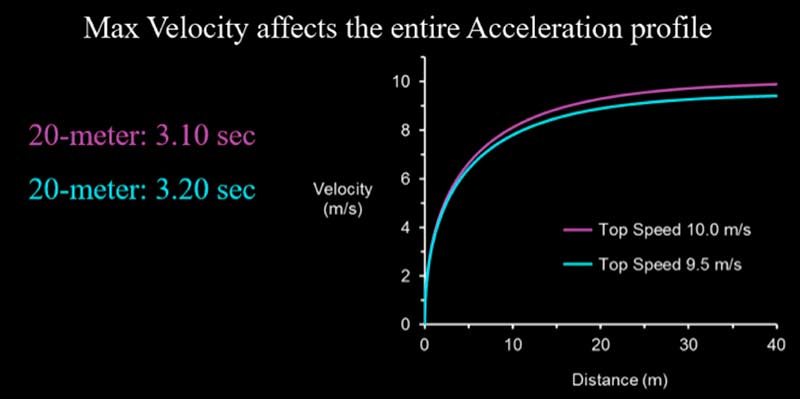

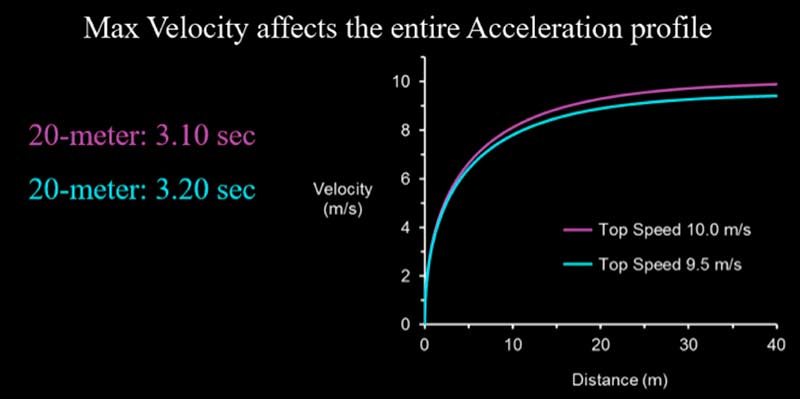

This chart from SprintCoach.com’s Derek Hansen is a great visual of the concept:

Carolina Panthers All-Pro running back Christian McCaffrey recently detailed how reducing his training volume and prioritizing his top-end speed has left him feeling both faster and fitter than ever.

“It’s obviously important to have a little speed endurance in football, but I’ve learned when I really condition myself hard, I feel myself kinda getting slower. And I’ll probably rub a lot of trainers wrong saying that. But I started doing (this) last year, and I can honestly say there were very few times I felt tired during a game,” McCaffrey, whose 326 total touches ranked third in the NFL last season, told STACK.

“I’ve tried everything. I feel like when I do (this), that’s when I feel the best.”

Eric Donoval, Associate Director of Sport Performance for Wyoming Football, says enhancing his athletes’ speed reserve is a major key to their conditioning.

“We want to get these guys’ absolute speed ceiling as high as possible, because that’s conditioning in and of itself. It’s really conditioning by speed reserve,” says Donoval.

“(The late Canadian sprint coach) Charlie Francis had a great quote about it. He said, ‘If you can’t touch the basketball rim, it really doesn’t matter how many times you can’t touch the basketball rim.’ So that’s a great depiction of what speed work needs to be…By increasing that maximal output, all sub-maximal outputs underneath that become faster and become easier on the body. You put a plow horse who can do really slow work for a long time next to a racehorse in a football game, the racehorse is going to win every time.”

Francis, a pioneer in speed development, frequently referred to a 95% “rule” for maximizing speed. He believed you must achieve 95% or better of your fastest time across a given distance for any sprint training to have a positive influence on your speed. For an athlete with a 4.40 40-Yard Dash PR, that means anything slower than a 4.62 across 40 yards isn’t genuine speed training. Consider how rarely most team sport athletes work in that top 5%, yet how often they train in the 60-80% range.

If I can run 23 mph and you can only run 18 mph, I can get tired and still run 19 mph. Your sorry ass is running at top speed and you can’t keep up with me. Then you get tired and you really suck. – @pntrack

— John Grace, MS (@john_r_grace) July 25, 2019

As Donoval’s athletes increased their max velocities throughout this offseason, he noticed how much faster their heart rates seemed to recover between reps of more traditional conditioning drills. He always programmed such drills for the end of the training week, so as not to let the resulting nervous system fatigue interfere with their strength, speed or power development. McCaffrey does the same.

“There are aspects of conditioning and change of direction and cutting under fatigue in football. So we do that later in the week after our high-quality days are already done,” Donoval told STACK in July.

“But what we’re starting to see is the recovery time between all these conditioning bouts—whether it’s an extensive tempo run or a 60-yard shuttle—we monitor their heart rates, and their recovery times are starting to drop dramatically because our team speed has increased. So our sub-maximal speed has also increased, (and) the energy requirement to do those repeat bouts is now less.”

Donoval says raising a football player’s speed ceiling while also mixing in an appropriate dose of more direct conditioning work is a “two-headed monster” for building relentless, capable athletes. For most coaches, that dose is going to be a lot smaller than they might be accustomed to.

“A lot of old-school coaches want to just run, run, run, but the absolute speed ceiling is what’s most important,” says Donoval.

Not only does a higher max speed improve conditioning, but it improves acceleration, too.

Team sport athletes rarely reach their max velocity during a game, but they often accelerate over short distances. Many team sport athletes spend a lot of time training short sprints and starts in the name of being more “sport-specific,” but enhancing their max velocity is an overlooked way to improve acceleration. And if they’re rarely running sprints longer than 10-15 yards, they’re never training max velocity.

Short acceleration can be improved with little to no impact on max speed, but the inverse is rarely true. This likely has to do with the changes in force application required to improve one’s max speed.

Obviously you have to accelerate to reach top speed, but acceleration plus max speed training seems to result in superior acceleration improvements compared to acceleration training alone. If you want to move faster over any distance, a higher max speed appears to be quite beneficial.

A 2019 study published in the Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research found that maximum velocity is of critical importance to 40-Yard Dash performance at the NFL Combine, in large part because of its strong correlation to splits at the 9.1 and 18.3 meter marks.

“Just a little improvement in top speed actually affects and enhances the entire acceleration profile,” Ken Clark, noted speed researcher and lead author of the aforementioned study, said during an appearance on The Strength Coach Podcast.

“We think about the first 20 yards being acceleration. That’s just kind of common thought or conventional wisdom—‘Well, if you’re doing a 20-yard dash, it’s acceleration.’…Small changes in top speed lead to big improvements in acceleration. A half-meter-per-second improvement in top speed would lead to a 10th-of-a-second improvement in a 20-Yard Dash time. It’d be over two 10ths of a second in a 40-Yard Dash. It’d be a big change in short sprint races.”

A slide from a Ken Clark presentation for ALTIS

The profound impact top speed has on acceleration could make it a relevant piece of the puzzle even for athletes, such as volleyball players, who compete on relatively small surfaces.

Developing speed takes a significant amount of time, planning and patience. Improving an athlete’s aerobic base and only their aerobic base requires much less thought and can be done quite quickly by comparison. Is an aerobic base needed in a sport like football? Undoubtedly. But that “bucket” is often overflowing while max speed is largely neglected. Furthermore, the best form of “conditioning” for any sport is actually playing the sport itself, which should be an integral part of practice.

How can coaches and athletes go about enhancing max speed?

That’s an entirely different conversation, but Clark’s research has found that most football players, regardless of position, reach around 93-96% of their max velocity by 20 yards into a 40-Yard Dash. Among other potential methods, consistently measuring an athlete’s 10-Yard Fly after a 20- or 30-yard run-in makes sense if enhancing max velocity is the goal. Cameron Josse, Director of Sports Performance at DeFranco’s Gym, wrote an excellent article on the topic of developing max velocity.

Conditioning drills like Suicides, Pole Runs and 110s are a time-honored tradition for team sport athletes. But they’re too often over-programmed and overvalued. Many coaches believe “suffering” is synonymous with “improvement,” which leads them to turn just about any training session or practice into a pain fest. And since this is “the way (they’ve) always done it,” they rarely stop to consider the effects.

On the whole, team sport athletes could benefit from less mindless conditioning and a greater focus on increasing max speed. While they may not often get the opportunity to hit that max speed during competition, the impact it has on elements that do determine winners and losers cannot be ignored.

Photo Credit: CHUYN/iStock

READ MORE:

RECOMMENDED FOR YOU

MOST POPULAR

The Top Speed Secret: Why Getting Faster Is the Ultimate Performance-Enhancer For Team Sport Athletes

Team sport athletes rarely reach max velocity during competition.

That’s just the reality. Fatigue becomes a factor shortly after the first whistle blows, and opportunities for the long, uninterrupted periods of linear sprinting needed to achieve max velocity rarely occur in the organic flow of a game.

So, in the name of being “sport-specific,” why even bother with max speed? Why not have team sport athletes get really good at running under fatigue, instead? That’s something we know will be unavoidable on game day, as the other team isn’t going to stop so you can “take a breather.” Mix in some short accelerations, which are much more common in competition for team sport athletes than long, max velocity sprints, and you’re good to go, right?

It sounds logical enough—which is exactly why this sort of thinking has been the default for team sport athletes for decades. Coaches say they want their players to get faster, but when it comes down to it, they’re really more worried about them being “out of shape.” That fear leads them to condition their athletes into oblivion.

Conditioning in the offseason. Conditioning before practice. Conditioning after practice. Conditioning during practice. Hustle to the next drill. Hustle to get water. Hustle back to the huddle. Hustle to get on the line for conditioning.

Many team sport athletes get lots and lots of exposure to fatigued sub-maximal running/training, yet very little exposure to max velocity. They get better at jogging while tired, but the high-volume takes a toll on their bodies.

What if instead of focusing on helping athletes maintain the likely mediocre speed they already possess, we shifted our perspective to making them truly faster? What if more speed was the ultimate trump card for outlasting an opponent?

Tony Holler, track coach at Plainfield North High School (Illinois) and inventor of the Feed the Cats methodology, is one man who’s shifting the paradigm when it comes to conditioning athletes.

“I’ve found conditioning to be the most over-used, over-valued, and counter-productive things in sport. In addition, it makes players slow,” Holler writes in a recent Track Football Consortium article on the topic.

“Conditioning is the act of intentionally getting athletes tired. And remember, ‘Any fool can get another fool tired.’”

Developing speed has long been a frustrating venture for many coaches. The main reasons for this, as Holler outlines in this STACK article, are athletes are made to run too far, too often and on too little rest to develop speed. Speed must also be a priority inside your program, not just something you wish for, and the simplest way to do that is by timing every sprint an athlete runs. When a number is attached to every effort, competition and intent skyrocket.

But an obsession with conditioning and “outworking” the opponent, which is especially prevalent in sports like football, often supersedes speed development. The norm becomes lots of work at 60-80% of max velocity, day after day. The body adapts to this implied demand, and players do get better at running gassers or 110s. But these adaptations do little for developing max speed (if anything, they tend to make you slower) and the constant high-volume work leaves players in a continuous state of exhaustion.

Most coaches view speed or conditioning as a one or the other proposition and, fearing the shame of having a “soft” team who didn’t work hard enough, consciously or subconsciously overvalue the latter.

But here’s the thing—enhancing your top speed is one of the best ways to enhance your conditioning, particularly for team sport athletes.

When your top speed increases, so does your speed reserve. Suddenly, what once represented 80% of your top speed might now represent 70%. Thus, the energy demands to achieve and maintain that speed are significantly reduced.

This chart from SprintCoach.com’s Derek Hansen is a great visual of the concept:

Carolina Panthers All-Pro running back Christian McCaffrey recently detailed how reducing his training volume and prioritizing his top-end speed has left him feeling both faster and fitter than ever.

“It’s obviously important to have a little speed endurance in football, but I’ve learned when I really condition myself hard, I feel myself kinda getting slower. And I’ll probably rub a lot of trainers wrong saying that. But I started doing (this) last year, and I can honestly say there were very few times I felt tired during a game,” McCaffrey, whose 326 total touches ranked third in the NFL last season, told STACK.

“I’ve tried everything. I feel like when I do (this), that’s when I feel the best.”

Eric Donoval, Associate Director of Sport Performance for Wyoming Football, says enhancing his athletes’ speed reserve is a major key to their conditioning.

“We want to get these guys’ absolute speed ceiling as high as possible, because that’s conditioning in and of itself. It’s really conditioning by speed reserve,” says Donoval.

“(The late Canadian sprint coach) Charlie Francis had a great quote about it. He said, ‘If you can’t touch the basketball rim, it really doesn’t matter how many times you can’t touch the basketball rim.’ So that’s a great depiction of what speed work needs to be…By increasing that maximal output, all sub-maximal outputs underneath that become faster and become easier on the body. You put a plow horse who can do really slow work for a long time next to a racehorse in a football game, the racehorse is going to win every time.”

Francis, a pioneer in speed development, frequently referred to a 95% “rule” for maximizing speed. He believed you must achieve 95% or better of your fastest time across a given distance for any sprint training to have a positive influence on your speed. For an athlete with a 4.40 40-Yard Dash PR, that means anything slower than a 4.62 across 40 yards isn’t genuine speed training. Consider how rarely most team sport athletes work in that top 5%, yet how often they train in the 60-80% range.

If I can run 23 mph and you can only run 18 mph, I can get tired and still run 19 mph. Your sorry ass is running at top speed and you can’t keep up with me. Then you get tired and you really suck. – @pntrack

— John Grace, MS (@john_r_grace) July 25, 2019

As Donoval’s athletes increased their max velocities throughout this offseason, he noticed how much faster their heart rates seemed to recover between reps of more traditional conditioning drills. He always programmed such drills for the end of the training week, so as not to let the resulting nervous system fatigue interfere with their strength, speed or power development. McCaffrey does the same.

“There are aspects of conditioning and change of direction and cutting under fatigue in football. So we do that later in the week after our high-quality days are already done,” Donoval told STACK in July.

“But what we’re starting to see is the recovery time between all these conditioning bouts—whether it’s an extensive tempo run or a 60-yard shuttle—we monitor their heart rates, and their recovery times are starting to drop dramatically because our team speed has increased. So our sub-maximal speed has also increased, (and) the energy requirement to do those repeat bouts is now less.”

Donoval says raising a football player’s speed ceiling while also mixing in an appropriate dose of more direct conditioning work is a “two-headed monster” for building relentless, capable athletes. For most coaches, that dose is going to be a lot smaller than they might be accustomed to.

“A lot of old-school coaches want to just run, run, run, but the absolute speed ceiling is what’s most important,” says Donoval.

Not only does a higher max speed improve conditioning, but it improves acceleration, too.

Team sport athletes rarely reach their max velocity during a game, but they often accelerate over short distances. Many team sport athletes spend a lot of time training short sprints and starts in the name of being more “sport-specific,” but enhancing their max velocity is an overlooked way to improve acceleration. And if they’re rarely running sprints longer than 10-15 yards, they’re never training max velocity.

Short acceleration can be improved with little to no impact on max speed, but the inverse is rarely true. This likely has to do with the changes in force application required to improve one’s max speed.

Obviously you have to accelerate to reach top speed, but acceleration plus max speed training seems to result in superior acceleration improvements compared to acceleration training alone. If you want to move faster over any distance, a higher max speed appears to be quite beneficial.

A 2019 study published in the Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research found that maximum velocity is of critical importance to 40-Yard Dash performance at the NFL Combine, in large part because of its strong correlation to splits at the 9.1 and 18.3 meter marks.

“Just a little improvement in top speed actually affects and enhances the entire acceleration profile,” Ken Clark, noted speed researcher and lead author of the aforementioned study, said during an appearance on The Strength Coach Podcast.

“We think about the first 20 yards being acceleration. That’s just kind of common thought or conventional wisdom—‘Well, if you’re doing a 20-yard dash, it’s acceleration.’…Small changes in top speed lead to big improvements in acceleration. A half-meter-per-second improvement in top speed would lead to a 10th-of-a-second improvement in a 20-Yard Dash time. It’d be over two 10ths of a second in a 40-Yard Dash. It’d be a big change in short sprint races.”

A slide from a Ken Clark presentation for ALTIS

The profound impact top speed has on acceleration could make it a relevant piece of the puzzle even for athletes, such as volleyball players, who compete on relatively small surfaces.

Developing speed takes a significant amount of time, planning and patience. Improving an athlete’s aerobic base and only their aerobic base requires much less thought and can be done quite quickly by comparison. Is an aerobic base needed in a sport like football? Undoubtedly. But that “bucket” is often overflowing while max speed is largely neglected. Furthermore, the best form of “conditioning” for any sport is actually playing the sport itself, which should be an integral part of practice.

How can coaches and athletes go about enhancing max speed?

That’s an entirely different conversation, but Clark’s research has found that most football players, regardless of position, reach around 93-96% of their max velocity by 20 yards into a 40-Yard Dash. Among other potential methods, consistently measuring an athlete’s 10-Yard Fly after a 20- or 30-yard run-in makes sense if enhancing max velocity is the goal. Cameron Josse, Director of Sports Performance at DeFranco’s Gym, wrote an excellent article on the topic of developing max velocity.

Conditioning drills like Suicides, Pole Runs and 110s are a time-honored tradition for team sport athletes. But they’re too often over-programmed and overvalued. Many coaches believe “suffering” is synonymous with “improvement,” which leads them to turn just about any training session or practice into a pain fest. And since this is “the way (they’ve) always done it,” they rarely stop to consider the effects.

On the whole, team sport athletes could benefit from less mindless conditioning and a greater focus on increasing max speed. While they may not often get the opportunity to hit that max speed during competition, the impact it has on elements that do determine winners and losers cannot be ignored.

Photo Credit: CHUYN/iStock

READ MORE: