What Do We Mean When We Say ‘Athletic?’

What is athletic?

Seriously, have you ever asked yourself exactly what it is that makes someone “athletic,” or what the definition of “athletic” actually is?

I’ll save you the trouble of looking it up and give you the definition right here—“physically strong, fit, active.” That didn’t really help us much, did it? Let’s take a look at some synonyms to see if that paints us a picture: muscular, muscly, sturdy, strapping, well built, strong, powerful, robust, able-bodied, vigorous, hardy, lusty, hearty, brawny, burly, heavily built, broad-shouldered, Herculean.

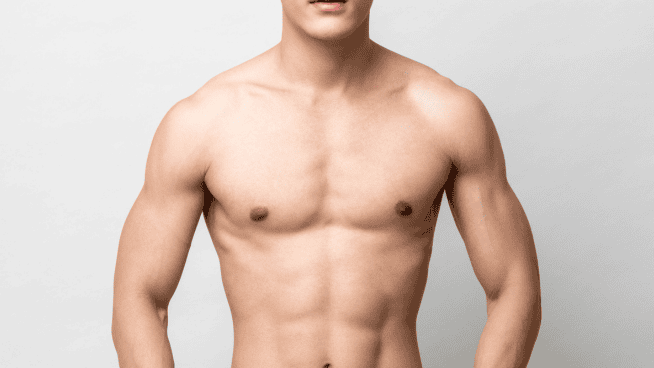

Hmm….so is this guy athletic?

He’s definitely large, muscular, well-built and most likely strong as heck. But I’m going to go out on a limb here and guess that no, he probably is not what we tend to think of athletic, even though he fits most of the standard definition.

Which takes us back to square one…

What is Athletic?

The question isn’t as easy to answer as you originally thought, right? I know, because I’ve been trying to answer this exact question for the last seven years as a strength and conditioning coach for young athletes.

Over the years, I’ve had the opportunity to speak with a variety of high school, college and even professional coaches on the topic and get their take on what they look for in an athlete. The only problem with that is what a coach is looking for is often specific to their sport, so they’re a bit biased. But If you listen closely, you will definitely hear a lot of similarities and underlining themes to the attributes coaches look for when recruiting players.

One of those attributes is mindset. “They have the mindset” is a phrase you’ll often hear coaches say in reference to the top athletes on their team. You will hear coaches talk about the “mental game” or the “mindset” required a lot. When they are recruiting new players, they are looking for a certain set of mental attributes that stand out. A few of these are going to be mental toughness, coachability, resilience, and positive outlook. So yeah, believe it or not, there are mental attributes that make up what it means to be athletic. The reality is that the mindset is the cornerstone to athletic ability and success in sports. Everything an athlete does and is capable of will eventually come back to their mindset.

You’ll also hear coaches refer to certain players as being “all-around athletes.” Here we go again with that broad term of “athlete” getting thrown around without a concrete understanding of what it actually means. For the purpose of this sentence, we will simply assume that an athlete is someone who plays sports. Therefore, an all-around athlete is someone who has a variety of abilities when it comes to sports. Simple Definition: An all-around athlete is someone who is multi-faceted and can perform well in a variety of sporting situations. They are not just limited to one sport or sporting scenario. Sounds official doesn’t it? Long story short, coaches are looking for players who are good at many things. Remember that.

We’ve already had two big breakthroughs in defining what it means to be athletic:

- We know that the center of an athlete’s athletic ability is going to be their mindset.

- We know that someone who is athletic is going to be proficient at a variety of abilities.

Now, it’s time to dive in to what exactly these abilities entail.

Speed

“Speed Kills.”

You’ve probably heard that phrase when it comes to sports, and it couldn’t be more true. Nine times out of 10, the faster athlete is going to be the more dominant athlete. Speed is going to allow them to move up and down the field or court faster as well as make shots, passes or any type of play at a more rapid rate. If you want to be considered athletic, you’re going to need some speed.

In the simplest form, speed is the measurement of how fast an athlete can get from point A to point B. When it comes to professional sports, this skill can be the difference between thousands of dollars or millions of dollars. In 2008, when Chris Johnson set a new standard for an electronically timed 40 -Yard Dash at 4.22 seconds, he moved his draft position from the 3rd round into the Top 25.

Functional Strength

Part of being athletic is to be strong; there is no doubt about that. But I think the important factor to note is that the strength must be functional. Even though the word “functional” has unfortunately turned into more of a marketing word these last 10 years, it still has its place in describing athletic ability. By “functional strength,” I mean that the athlete is strong in a way that’s beneficial to their abilities on the field, court, ice, etc.

When I was 16 years old, I could Bench Press 300-plus pounds but could not Squat 225 pounds. As a running back on my local high school football team, my 300-pound Bench Press was not very functional. Sure, the meatheads at my gym thought it was cool that this kid could bench so much weight, but it didn’t mean jack on the football field. Thankfully, I quickly found out that my leg strength was much more functional than my chest strength.

The most athletic individuals in the world have full-body strength that allows them to move with precise control in multiple planes at various angles and at different speeds. They have the ability to slow themselves or an external force down and speed it back up in the most efficient manner. Believe it or not, an athlete’s ability to develop high levels of functional strength is also going to be reliant on their flexibility and power output capabilities (you’ll see that each athletic ability is somewhat reliant on the others).

Power

It’s time to combine that speed and functional strength to produce some serious power. Power is another staple in the athletic repertoire. Power is simply the ability to move an object over a distance in minimal time. Simple examples include sprinting, jumping or throwing, and someone who is athletic should be able to do all three.

A true athlete has the ability to take that speed and strength and put it into motion, whether it is with their own body weight or an external object. Yes, there are professional athletes who can’t jump high or throw far, but just because they made it to the pros doesn’t necessarily mean they are athletic.

Flexibility

Flexibility refers to the range of motion in a joint both statically and dynamically, looking specifically at the soft tissue that surrounds the joint. Although optimal flexibility is different from athlete to athlete, obtaining a good level of flexibility is going to be a prerequisite for someone who is athletic.

For an athlete to develop optimal strength and power, they are going to need to be able to move through the full range of motion at each joint. Athletes with better flexibility also exhibit a reduction in the incidence of injury, decreases in severity of injuries, and delays in the onset of muscular fatigue.

Don’t believe me? Just take a look at the top-level gymnasts who possess impressive amounts of strength, power and flexibility, all at once. I’d say that’s pretty darn athletic.

Agility

Isn’t agility the same thing as speed?

Not exactly. When we’re talking agility for an athlete, you want to think more along the lines of movement in space. Specifically, how well does an athlete’s body react to an external stimulus by changing velocity or direction? A 100-meter track star will be fast, but they might not be agile.

A player who is athletic has the ability to move in ways that sometimes confuse our brains in attempting to comprehend them. They can stop on a dime and cut at angles and speeds that would cause most of us to stumble face first into the ground.

“Reactive” agility, or how well an athlete is able to respond through movement to an external stimulus, is what really makes a key distinction between the most and least athletic players on the field. It’s one thing to run around some cones with tight corners, but it’s a whole other ball game when there is a defender chasing you down and you have to react with your movement.

The best of the best are able to make those split-second decisions and reactive movements look easy.

Mobility

Mobility in a joint refers to the range of motion in a specific joint, as well, but it is determined not just by the flexibility of the tissues surrounding that joint, but also by the motor-unit activity in the surrounding muscle groups.

To have mobility in a specific joint, the soft-tissue surrounding that joint will have to exhibit certain degrees of flexibility to move throughout the full range of motion. For an athlete to hit the proper positions in sport and exercise, they have to develop the proper flexibility throughout the joints of their body.

The second piece of mobility, however, is focused on looking at the motor unit activity in the joint. For our purposes, think of this as “strength” or “activity” within a particular joint. This second portion is often overlooked when investigating the mobility of an athlete. Yes, it’s important to have the proper range of motion, but someone who is athletic will also have the ability to remain active throughout the full range of motion. This means they’ll be able to exhibit strength in all positions throughout the full range of motion of the joint. This is much different than just passive mobility, where a joint is capable of full range of motion as long as there is no activity at that joint.

Example: Say we take someone who can’t squat to full depth and have them lie on the floor and put their feet up against the wall. Then have the individual slide themselves closer to the wall into a “deep squat position.” If they can reach the position while lying on the floor but not while standing, then we know that they have passive mobility, but not the strength to be active in that position.

Recovery

The final piece to the puzzle of what it means to be athletic is the recovery factor. The truth is that being able to perform and exhibit high levels of skill is relatively useless if your body can’t recover properly to do it all again tomorrow. It’s like the car that can go super fast but has no brakes and a hole in its fuel tank. In time, that super fast car will be useless.

Recovery should also be multi-faceted, meaning that the athlete is capable of recovering adequately from a variety of stimuli.

What does that mean?

In 1979, Zalessky distinguished between three different types of recovery when it comes to sport or training:

- On-going Recovery, which takes place during the activity

- Rapid recovery, which occurs immediately after exercise and focuses on removal of metabolic waste and replenishment of depleted depleted energy sources

- Delayed recovery, which is the long-term phase of recovery that allows an athlete to surpass previous training levels

Top-level athletes and the most athletic people in the world are able to exhibit all three types of recovery.

When you break it all down, the question “What is Athletic?” turns out to be a loaded one. If you look at the course of history and the evolution of sport, you will clearly see that the definition of “athletic” has evolved over time and will continue to do so with the changes in how each sport is played. Take hockey, for example. In today’s game, the role of a “fighter” or “bruiser” is getting smaller and smaller as the game speed gets faster and players become more skilled. As the game has evolved, so has the athletic abilities that are desired within it.

So why does this all matter?

Well, in order to compete at the highest level, the training you go through will have to prepare you to handle the athletic demands of your modern sport. This means that the way your dad trained 25 years ago is most likely not as relevant today. Training approaches need to evolve with sport.

Be on the lookout for part two in this series, in which I’ll explain how to train to be athletic.

Photo Credit: MRBIG_PHOTOGRAPHY/iStock, simonkr/iStock, groveb/iStock, FS-Stock,iStock, strickke/iStock, bernardbodo/iStock

READ MORE:

RECOMMENDED FOR YOU

MOST POPULAR

What Do We Mean When We Say ‘Athletic?’

What is athletic?

Seriously, have you ever asked yourself exactly what it is that makes someone “athletic,” or what the definition of “athletic” actually is?

I’ll save you the trouble of looking it up and give you the definition right here—“physically strong, fit, active.” That didn’t really help us much, did it? Let’s take a look at some synonyms to see if that paints us a picture: muscular, muscly, sturdy, strapping, well built, strong, powerful, robust, able-bodied, vigorous, hardy, lusty, hearty, brawny, burly, heavily built, broad-shouldered, Herculean.

Hmm….so is this guy athletic?

He’s definitely large, muscular, well-built and most likely strong as heck. But I’m going to go out on a limb here and guess that no, he probably is not what we tend to think of athletic, even though he fits most of the standard definition.

Which takes us back to square one…

What is Athletic?

The question isn’t as easy to answer as you originally thought, right? I know, because I’ve been trying to answer this exact question for the last seven years as a strength and conditioning coach for young athletes.

Over the years, I’ve had the opportunity to speak with a variety of high school, college and even professional coaches on the topic and get their take on what they look for in an athlete. The only problem with that is what a coach is looking for is often specific to their sport, so they’re a bit biased. But If you listen closely, you will definitely hear a lot of similarities and underlining themes to the attributes coaches look for when recruiting players.

One of those attributes is mindset. “They have the mindset” is a phrase you’ll often hear coaches say in reference to the top athletes on their team. You will hear coaches talk about the “mental game” or the “mindset” required a lot. When they are recruiting new players, they are looking for a certain set of mental attributes that stand out. A few of these are going to be mental toughness, coachability, resilience, and positive outlook. So yeah, believe it or not, there are mental attributes that make up what it means to be athletic. The reality is that the mindset is the cornerstone to athletic ability and success in sports. Everything an athlete does and is capable of will eventually come back to their mindset.

You’ll also hear coaches refer to certain players as being “all-around athletes.” Here we go again with that broad term of “athlete” getting thrown around without a concrete understanding of what it actually means. For the purpose of this sentence, we will simply assume that an athlete is someone who plays sports. Therefore, an all-around athlete is someone who has a variety of abilities when it comes to sports. Simple Definition: An all-around athlete is someone who is multi-faceted and can perform well in a variety of sporting situations. They are not just limited to one sport or sporting scenario. Sounds official doesn’t it? Long story short, coaches are looking for players who are good at many things. Remember that.

We’ve already had two big breakthroughs in defining what it means to be athletic:

- We know that the center of an athlete’s athletic ability is going to be their mindset.

- We know that someone who is athletic is going to be proficient at a variety of abilities.

Now, it’s time to dive in to what exactly these abilities entail.

Speed

“Speed Kills.”

You’ve probably heard that phrase when it comes to sports, and it couldn’t be more true. Nine times out of 10, the faster athlete is going to be the more dominant athlete. Speed is going to allow them to move up and down the field or court faster as well as make shots, passes or any type of play at a more rapid rate. If you want to be considered athletic, you’re going to need some speed.

In the simplest form, speed is the measurement of how fast an athlete can get from point A to point B. When it comes to professional sports, this skill can be the difference between thousands of dollars or millions of dollars. In 2008, when Chris Johnson set a new standard for an electronically timed 40 -Yard Dash at 4.22 seconds, he moved his draft position from the 3rd round into the Top 25.

Functional Strength

Part of being athletic is to be strong; there is no doubt about that. But I think the important factor to note is that the strength must be functional. Even though the word “functional” has unfortunately turned into more of a marketing word these last 10 years, it still has its place in describing athletic ability. By “functional strength,” I mean that the athlete is strong in a way that’s beneficial to their abilities on the field, court, ice, etc.

When I was 16 years old, I could Bench Press 300-plus pounds but could not Squat 225 pounds. As a running back on my local high school football team, my 300-pound Bench Press was not very functional. Sure, the meatheads at my gym thought it was cool that this kid could bench so much weight, but it didn’t mean jack on the football field. Thankfully, I quickly found out that my leg strength was much more functional than my chest strength.

The most athletic individuals in the world have full-body strength that allows them to move with precise control in multiple planes at various angles and at different speeds. They have the ability to slow themselves or an external force down and speed it back up in the most efficient manner. Believe it or not, an athlete’s ability to develop high levels of functional strength is also going to be reliant on their flexibility and power output capabilities (you’ll see that each athletic ability is somewhat reliant on the others).

Power

It’s time to combine that speed and functional strength to produce some serious power. Power is another staple in the athletic repertoire. Power is simply the ability to move an object over a distance in minimal time. Simple examples include sprinting, jumping or throwing, and someone who is athletic should be able to do all three.

A true athlete has the ability to take that speed and strength and put it into motion, whether it is with their own body weight or an external object. Yes, there are professional athletes who can’t jump high or throw far, but just because they made it to the pros doesn’t necessarily mean they are athletic.

Flexibility

Flexibility refers to the range of motion in a joint both statically and dynamically, looking specifically at the soft tissue that surrounds the joint. Although optimal flexibility is different from athlete to athlete, obtaining a good level of flexibility is going to be a prerequisite for someone who is athletic.

For an athlete to develop optimal strength and power, they are going to need to be able to move through the full range of motion at each joint. Athletes with better flexibility also exhibit a reduction in the incidence of injury, decreases in severity of injuries, and delays in the onset of muscular fatigue.

Don’t believe me? Just take a look at the top-level gymnasts who possess impressive amounts of strength, power and flexibility, all at once. I’d say that’s pretty darn athletic.

Agility

Isn’t agility the same thing as speed?

Not exactly. When we’re talking agility for an athlete, you want to think more along the lines of movement in space. Specifically, how well does an athlete’s body react to an external stimulus by changing velocity or direction? A 100-meter track star will be fast, but they might not be agile.

A player who is athletic has the ability to move in ways that sometimes confuse our brains in attempting to comprehend them. They can stop on a dime and cut at angles and speeds that would cause most of us to stumble face first into the ground.

“Reactive” agility, or how well an athlete is able to respond through movement to an external stimulus, is what really makes a key distinction between the most and least athletic players on the field. It’s one thing to run around some cones with tight corners, but it’s a whole other ball game when there is a defender chasing you down and you have to react with your movement.

The best of the best are able to make those split-second decisions and reactive movements look easy.

Mobility

Mobility in a joint refers to the range of motion in a specific joint, as well, but it is determined not just by the flexibility of the tissues surrounding that joint, but also by the motor-unit activity in the surrounding muscle groups.

To have mobility in a specific joint, the soft-tissue surrounding that joint will have to exhibit certain degrees of flexibility to move throughout the full range of motion. For an athlete to hit the proper positions in sport and exercise, they have to develop the proper flexibility throughout the joints of their body.

The second piece of mobility, however, is focused on looking at the motor unit activity in the joint. For our purposes, think of this as “strength” or “activity” within a particular joint. This second portion is often overlooked when investigating the mobility of an athlete. Yes, it’s important to have the proper range of motion, but someone who is athletic will also have the ability to remain active throughout the full range of motion. This means they’ll be able to exhibit strength in all positions throughout the full range of motion of the joint. This is much different than just passive mobility, where a joint is capable of full range of motion as long as there is no activity at that joint.

Example: Say we take someone who can’t squat to full depth and have them lie on the floor and put their feet up against the wall. Then have the individual slide themselves closer to the wall into a “deep squat position.” If they can reach the position while lying on the floor but not while standing, then we know that they have passive mobility, but not the strength to be active in that position.

Recovery

The final piece to the puzzle of what it means to be athletic is the recovery factor. The truth is that being able to perform and exhibit high levels of skill is relatively useless if your body can’t recover properly to do it all again tomorrow. It’s like the car that can go super fast but has no brakes and a hole in its fuel tank. In time, that super fast car will be useless.

Recovery should also be multi-faceted, meaning that the athlete is capable of recovering adequately from a variety of stimuli.

What does that mean?

In 1979, Zalessky distinguished between three different types of recovery when it comes to sport or training:

- On-going Recovery, which takes place during the activity

- Rapid recovery, which occurs immediately after exercise and focuses on removal of metabolic waste and replenishment of depleted depleted energy sources

- Delayed recovery, which is the long-term phase of recovery that allows an athlete to surpass previous training levels

Top-level athletes and the most athletic people in the world are able to exhibit all three types of recovery.

When you break it all down, the question “What is Athletic?” turns out to be a loaded one. If you look at the course of history and the evolution of sport, you will clearly see that the definition of “athletic” has evolved over time and will continue to do so with the changes in how each sport is played. Take hockey, for example. In today’s game, the role of a “fighter” or “bruiser” is getting smaller and smaller as the game speed gets faster and players become more skilled. As the game has evolved, so has the athletic abilities that are desired within it.

So why does this all matter?

Well, in order to compete at the highest level, the training you go through will have to prepare you to handle the athletic demands of your modern sport. This means that the way your dad trained 25 years ago is most likely not as relevant today. Training approaches need to evolve with sport.

Be on the lookout for part two in this series, in which I’ll explain how to train to be athletic.

Photo Credit: MRBIG_PHOTOGRAPHY/iStock, simonkr/iStock, groveb/iStock, FS-Stock,iStock, strickke/iStock, bernardbodo/iStock

READ MORE: