What Is ‘Load Management’ and Why Does it Matter for Athletes?

Fans, coaches and developing athletes throughout the world now have yet another term to tackle and decipher: load management.

Throughout this NBA season, we have witnessed the deliberate shelving of some of the game’s biggest superstars, including LeBron James, Kawhi Leonard, Anthony Davis and Joel Embiid. The reason? Load management.

Recommending what appears to be some old-fashioned “rest and relaxation” is purported to improve athlete health and performance and prolong careers. But load management strategies extend beyond the aforementioned shortlist of the NBA’s elite, permeating the ranks of lesser ballyhooed ballers and throughout the college and high school levels.

What Is Load Management?

Load management is defined as the deliberate temporary reduction of external physiological stressors intended to facilitate global improvements in athlete wellness and performance while preserving musculoskeletal and metabolic health. Basically, you reduce the amount of training and/or competition an athlete takes on to help them recover better and perform better over the long term.

RELATED: 5 Sports Health Tips to Extend Your Athletic Career

Why Basketball Players Need Load Management

A basketball season is a downright grind. Players at all levels are subject to seemingly endless competitive periods characterized by protracted preseason play, exhibition games, and ever growing postseasons with qualifying games and a maze of tournaments. Additionally, the accessibility to practicing and playing throughout the year and promotion of extracurricular competition are not conducive to establishing a definitive offseason. The cumulative wear and tear taxes muscles and erodes the integrity of the body’s delicate architecture of bones, joints and ligaments.

Basketball, particularly at higher levels, is an incredibly demanding sport. A 1995 analysis of elite basketball players throughout a 48-minute contest revealed that roughly a quarter of the game is spent exerting near maximal outputs of speed, power and strength. Many NBA starters run roughly 2.5 miles per game, with much of that distance being at high intensity. Average heart rates exceeded 85% of HR Max for 75% of the game. Those logging 36 minutes of playing time, or “starter minutes,” registered an average of 70 jumps per game.

RELATED: How Cutting Back on Your Workouts Can Actually Make You Stronger

Throughout the course of a season, starting men’s Division I basketball players were exposed to significantly high cumulative, or chronic, workloads (quantified by running distance and number of jumps) by virtue of competition, practice and training sessions. Research has shown that workloads were correlated with the number of games scheduled within the week. It was also revealed that workloads were lower over a two-week period versus a one-week period, since stressors are not as condensed and can be more readily manipulated during longer competitive or training blocks. Players who experience an uptick in playing time or receive “starter minutes” are subjected to greater acute workloads, or competitive stressors for which they were not previously accustomed.

The Cautionary Tale of Kobe Bryant

Kobe Bryant recently ripped the idea of NBA players missing games in the name of load management. “The only time I took a game off is when I couldn’t walk…If you can walk and perform, get there and perform,” Bryant told The Athletic.

In an attempt to propel the 2012-2013 Lakers to the playoffs through a crowded Western Conference, Kobe Bryant, in his 17th pro season, logged 38.6 minutes per game, second-most in the league. Luol Deng, more than six years his junior, ranked first at 38.7 minutes per game.

If anyone was in need of load management it was Kobe. Leading up to that season he’d registered 42,377 minutes throughout his career, not counting his brutal and daily marathon practice and training sessions. By comparison, Lebron James, who earned his share of criticism for resting this season (which was his 17th) had registered 44,298 minutes in the same career span.

Unfortunately, the Lakers championship hopes and to a greater extent, Kobe’s reign as a member of the NBA’s elite, were ended by a torn Achilles tendon that season. There’s no doubt Kobe is one of the greatest players in history, but the idea that you should play as long as you can walk is just silly. We don’t want to see any athlete suffer a significant injury before the games that count the most. It’d be great if every athlete was a superhuman incapable of getting fatigued or injured, but it’s just not real life. That’s why we need to embrace the practice of load management.

How to Calculate Your Load

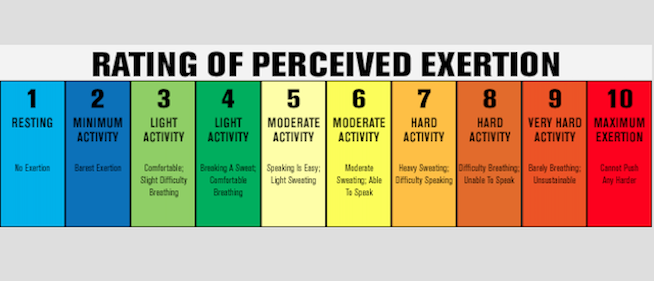

Load management starts with calculating work load. Although the majority of athletes and coaches do not have sophisticated equipment to measure biomarkers associated with fatigue and global positioning systems to accurately monitor running distance, acceleration, and vertical or horizontal displacement throughout practices and games, stress can still be quantified utilizing a rating of perceived exertion (RPE) scale, a valuable tool to measure the intensity of physical activity. The scale runs from 1 through 10, with 10 defined as maximal exertion, meaning that one cannot push any harder:

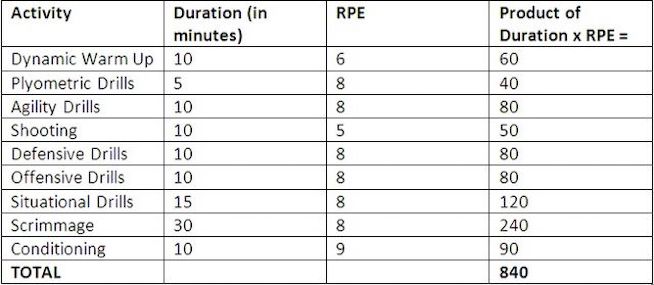

To calculate workload, one can multiply their average RPE by the number of minutes they are performing a given drill or exercise. For example, a basketball player engaging in a practice session would rate each portion of practice accordingly, with each score being multiplied by the number of minutes spent on that portion:

Coaches and players can use this tactic to establish baseline data for practices, games and periods throughout the season.

The Importance of Deloading

Deload periods, also known as “unloading” or “offloading,” are characterized by a deliberately planned reduction in one or a number of parameters, including frequency, intensity, time and type of activity.

For student-athletes, weeks during the season in which they will be facing competitive demands, such as exams, due dates for papers and projects, or extensive travel by car, bus or plane, would be the perfect opportunity to scale back one or more of the aforementioned parameters.

Load management might be a term that’s taken on some negative connotations, but the truth is it’s hugely important for any athlete looking to consistently compete at a high level and stay injury free.

Photo Credit: curtis_creative/iStock

READ MORE:

RECOMMENDED FOR YOU

MOST POPULAR

What Is ‘Load Management’ and Why Does it Matter for Athletes?

Fans, coaches and developing athletes throughout the world now have yet another term to tackle and decipher: load management.

Throughout this NBA season, we have witnessed the deliberate shelving of some of the game’s biggest superstars, including LeBron James, Kawhi Leonard, Anthony Davis and Joel Embiid. The reason? Load management.

Recommending what appears to be some old-fashioned “rest and relaxation” is purported to improve athlete health and performance and prolong careers. But load management strategies extend beyond the aforementioned shortlist of the NBA’s elite, permeating the ranks of lesser ballyhooed ballers and throughout the college and high school levels.

What Is Load Management?

Load management is defined as the deliberate temporary reduction of external physiological stressors intended to facilitate global improvements in athlete wellness and performance while preserving musculoskeletal and metabolic health. Basically, you reduce the amount of training and/or competition an athlete takes on to help them recover better and perform better over the long term.

RELATED: 5 Sports Health Tips to Extend Your Athletic Career

Why Basketball Players Need Load Management

A basketball season is a downright grind. Players at all levels are subject to seemingly endless competitive periods characterized by protracted preseason play, exhibition games, and ever growing postseasons with qualifying games and a maze of tournaments. Additionally, the accessibility to practicing and playing throughout the year and promotion of extracurricular competition are not conducive to establishing a definitive offseason. The cumulative wear and tear taxes muscles and erodes the integrity of the body’s delicate architecture of bones, joints and ligaments.

Basketball, particularly at higher levels, is an incredibly demanding sport. A 1995 analysis of elite basketball players throughout a 48-minute contest revealed that roughly a quarter of the game is spent exerting near maximal outputs of speed, power and strength. Many NBA starters run roughly 2.5 miles per game, with much of that distance being at high intensity. Average heart rates exceeded 85% of HR Max for 75% of the game. Those logging 36 minutes of playing time, or “starter minutes,” registered an average of 70 jumps per game.

RELATED: How Cutting Back on Your Workouts Can Actually Make You Stronger

Throughout the course of a season, starting men’s Division I basketball players were exposed to significantly high cumulative, or chronic, workloads (quantified by running distance and number of jumps) by virtue of competition, practice and training sessions. Research has shown that workloads were correlated with the number of games scheduled within the week. It was also revealed that workloads were lower over a two-week period versus a one-week period, since stressors are not as condensed and can be more readily manipulated during longer competitive or training blocks. Players who experience an uptick in playing time or receive “starter minutes” are subjected to greater acute workloads, or competitive stressors for which they were not previously accustomed.

The Cautionary Tale of Kobe Bryant

Kobe Bryant recently ripped the idea of NBA players missing games in the name of load management. “The only time I took a game off is when I couldn’t walk…If you can walk and perform, get there and perform,” Bryant told The Athletic.

In an attempt to propel the 2012-2013 Lakers to the playoffs through a crowded Western Conference, Kobe Bryant, in his 17th pro season, logged 38.6 minutes per game, second-most in the league. Luol Deng, more than six years his junior, ranked first at 38.7 minutes per game.

If anyone was in need of load management it was Kobe. Leading up to that season he’d registered 42,377 minutes throughout his career, not counting his brutal and daily marathon practice and training sessions. By comparison, Lebron James, who earned his share of criticism for resting this season (which was his 17th) had registered 44,298 minutes in the same career span.

Unfortunately, the Lakers championship hopes and to a greater extent, Kobe’s reign as a member of the NBA’s elite, were ended by a torn Achilles tendon that season. There’s no doubt Kobe is one of the greatest players in history, but the idea that you should play as long as you can walk is just silly. We don’t want to see any athlete suffer a significant injury before the games that count the most. It’d be great if every athlete was a superhuman incapable of getting fatigued or injured, but it’s just not real life. That’s why we need to embrace the practice of load management.

How to Calculate Your Load

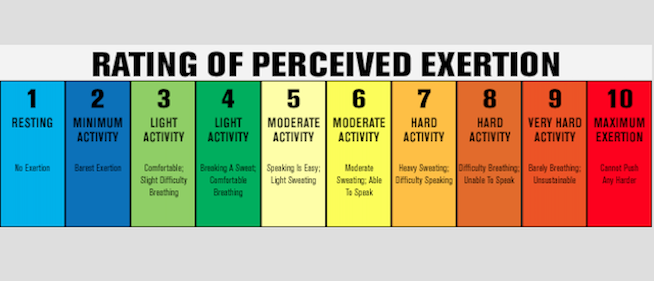

Load management starts with calculating work load. Although the majority of athletes and coaches do not have sophisticated equipment to measure biomarkers associated with fatigue and global positioning systems to accurately monitor running distance, acceleration, and vertical or horizontal displacement throughout practices and games, stress can still be quantified utilizing a rating of perceived exertion (RPE) scale, a valuable tool to measure the intensity of physical activity. The scale runs from 1 through 10, with 10 defined as maximal exertion, meaning that one cannot push any harder:

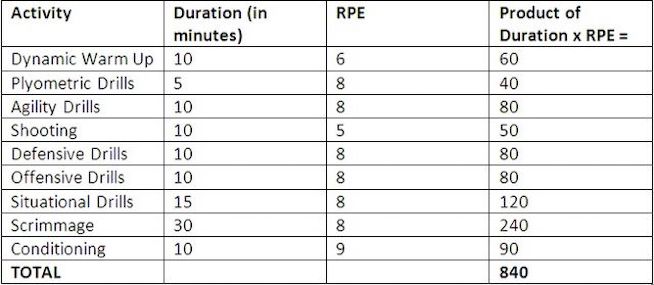

To calculate workload, one can multiply their average RPE by the number of minutes they are performing a given drill or exercise. For example, a basketball player engaging in a practice session would rate each portion of practice accordingly, with each score being multiplied by the number of minutes spent on that portion:

Coaches and players can use this tactic to establish baseline data for practices, games and periods throughout the season.

The Importance of Deloading

Deload periods, also known as “unloading” or “offloading,” are characterized by a deliberately planned reduction in one or a number of parameters, including frequency, intensity, time and type of activity.

For student-athletes, weeks during the season in which they will be facing competitive demands, such as exams, due dates for papers and projects, or extensive travel by car, bus or plane, would be the perfect opportunity to scale back one or more of the aforementioned parameters.

Load management might be a term that’s taken on some negative connotations, but the truth is it’s hugely important for any athlete looking to consistently compete at a high level and stay injury free.

Photo Credit: curtis_creative/iStock

READ MORE: