Why I Stopped Back Squatting My Athletes

This article is for team sport athletes, not powerlifters.

I don’t believe the Barbell Back Squat is the best way to train team sport athletes. I know that might sound crazy, but I ask that you read with an open mind and consider the points I raise here. The nuances of team sport athletics require thinking outside the box of traditional strength training. My argument that the Barbell Back Squat is not the best choice for most team sport athletes revolves around four key points: Torso Angle, Muscle Activation, Ankle Mobility and Safety. I’m writing this as a strength and conditioning coach who trains high school athletes, mostly of the team sport variety. Some of the issues I raise here might not necessarily apply to a “perfect” back squatter, but the reality is that the overwhelming majority of team sport athletes are not perfect back squatters.

1. Torso Angle Too Far Forward

The location of the bar during the Back Squat forces the torso to come forward to keep the weight over the athlete’s mid foot. Athletes with great mobility are able to have a more vertical torso in the Back Squat, but the majority of athletes will need to hinge more at their hips to maintain balance over the mid foot. This significantly increases the load on the low back, which is one of the most important areas to protect when strength training.

Secondly, as the torso comes forward, this will cause contraction of the hamstrings, which will make it more difficult to get below parallel with proper form on your Squats. I will explain why this is so significant later on.

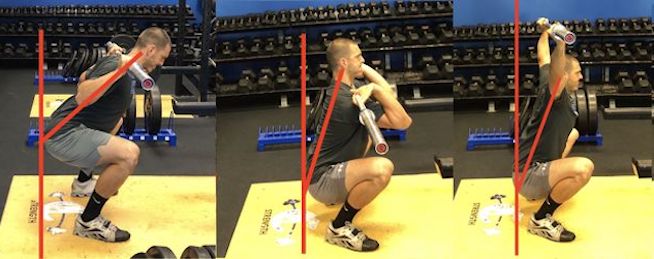

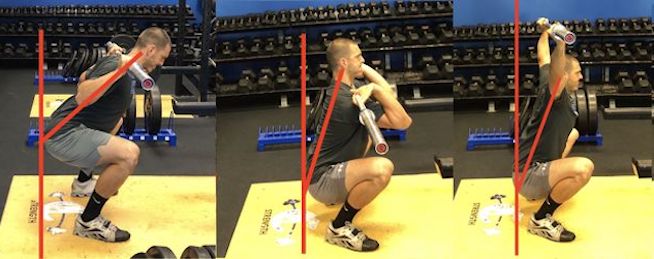

Approximate torso angles I typically see on Back Squat/Front Squat/Overhead Squat

I find the Back Squat often leads team sport athletes to have too forward a torso angle for my liking.

2. Glutes Not Getting Involved

Many coaches tout the Back Squat for its ability to engage all the muscles of the lower body in one coordinated movement. While in theory that is true, for the majority of athletes it’s not quite accurate to what happens in practice. As I stated above, the forward torso angle many athletes demonstrate in the Back Squat often makes it more difficult to get below parallel. The reason this matters is that research has shown that the glutes don’t see significant activation until the athlete gets below parallel. This means that the athlete is likely relying almost entirely on the hamstrings for hip extension.

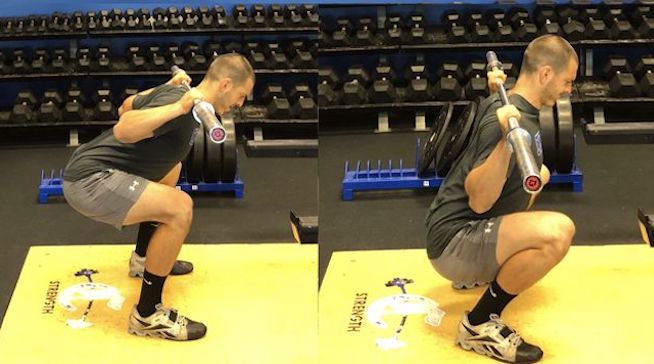

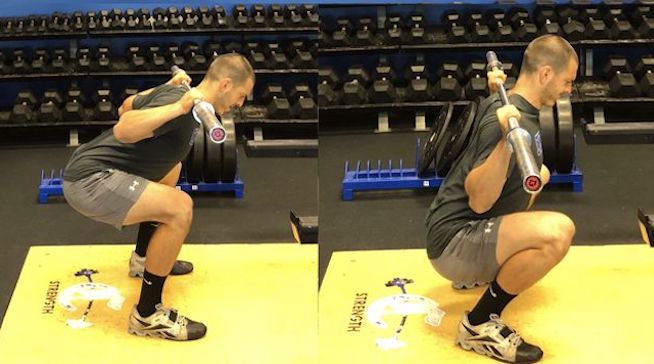

Hamstring-Dependent Back Squat vs Glute-Dependent Back Squat

Why does it matter if an athlete has strong hamstrings and weak, inactive glutes? The hamstrings work at both the knee (as flexors) and the hip (as synergists to extension). When the hamstrings are forced to be prime movers both at the hip and knee, you increase the risk of sustaining a hamstring strain. Inactive glutes have also been linked to other common athletic injuries, such as Patellar Tendonitis and ACL/MCL Tears. For this reason, I personally will not use any exercise that increases the hamstrings role at the hip at the expense of glute function. In my eyes, the Back Squat is the most common culprit of this.

3. The Ripple Effect of Poor Ankle Mobility

I get mocked mercilessly by my athletes for my love of ankle mobility. However, there’s a reason I obsess over it so much. The ankle is the first major link in the kinetic chain. Connected to the foot, it is the first major joint to contact the ground during land-based athletic movements like running and jumping. If there is something wrong with the ankle, it is going to cause issues all the way up the chain. Sufficient ankle mobility is crucial for athletic performance and injury prevention. Along with improper glute function, research has begun to show correlations between limitations in ankle dorsiflexion and non-contact ACL Tears. The reason ankle mobility can be a strike against the Back Squat is because the exercise is perhaps the only squat variation that allows you to compensate for a lack of ankle mobility.

In the Back Squat, athletes can hinge at their torso to compensate or work around limited movement at the ankle. Instead of training the ankle to move, this actually works to reduce overall motion at the ankle. I see too many athletes fall victim to something that looks like this on the Back Squat, where they compensate for a lack of ankle mobility by sitting back to load the low back and depend on the strength of the hamstrings rather than the glutes (compared to the level of ankle mobility I often see in a Front Squat) :

As you see in the Front and Overhead Squat Images, there’s a lot more ankle mobility being displayed. Again, these are not issues with a “perfect” back squatter, but they are issues I frequently see crop up for team sport athletes.

4. Not as Safe as You Might Think

For any strength and conditioning coach, every programmed exercise must be weighed on the risk-reward continuum. For example; while the Single-Arm, Single-Leg Overhead Squat may have plenty of benefits for strength, stability, balance and coordination, it’s probably not the safest option. In my opinion, the risks outweigh the rewards. I tell my athletes that there will always come a point that you will fail in the weight room. As a strength coach, I need to take precautions for when that occurs.

If an athlete fails on the Back Squat, things can get risky pretty quickly. Yes, you can use pins—but many high school weight rooms don’t have them. Yes, spotters will make it less dangerous, but most high school students have a tough time even knowing when they’re going to require a spotter. I also have very little faith in a high school male taking seriously the importance of their role as a spotter, which puts both the lifter and the spotter at risk of injury. With highly trained athletes who know their limits and who are working in an environment where pins are available and every spotter takes their job seriously, the risk is a lot lower. But in your average high school weight room, the reality is that the Back Squat is not the safest of exercises.

The combination of all four issues led me to seriously rethink if it was worthing having the Back Squat in my programs. But if not the Back Squat, then what? For me, the answer I came to was the Front Squat.

Why I Love the Front Squat for my Athletes

I personally believe the Front Squat is superior in all four categories outlined above while maintaining all the benefits of a bilateral movement. It’s a much safer variation, because when an athlete fails, they simply “bail” the bar in front of them. A spotter is completely superfluous; you simply don’t need one during front squatting. The Front Squat, as shown in the photos above, also has a more vertical torso angle, which reduces the load on the lumbar spine. Due to that torso angle, hip movement is more easily driven by the glutes than it is the hamstrings. This is highly advantageous for athletes who struggle with firing their glutes. I also believe it’s much easier to get below parallel in the Front Squat, which is where glute activity really occurs in squatting.

The Front Squat isn’t nearly as technical as the Overhead Squat and it’s more conducive to good positions than the Back Squat. Lastly, it is nearly impossible to compensate for a lack of ankle mobility in a Front Squat. If the athlete lacks sufficient ankle dorsiflexion, their torso falls forward, causing the bar to roll off of their shoulders. The athlete is forced to address their mobility issues instead of compensating for them. While most athletes cannot Front Squat quite as much as they can Back Squat, you can still load it plenty heavy. And since it’s much harder to “cheat” a Front Squat than a Back Squat, athletes are more likely to use appropriate weights. Quite simply, it’s a lot harder to mess up a Front Squat than it is a Back Squat.

For these reasons, I believe the Front Squat is the superior bilateral squat. Do I still Back Squat with my athletes? Yes, but only as a change-of-pace lift in the offseason. Never during the preseason or in season. In my experience, the risk is simply not worth the reward to do them more often than that, as the Front Squat accomplishes what I want to accomplish in a safer, more effective manner.

References:

- Barton, Christian J., Simon Lack, Peter Malliaras, and Dylan Morrissey. “Gluteal Muscle Activity and Patellofemoral Pain Syndrome: A Systematic Review.” British Journal of Sports Medicine 47.4 (2012): 207-14. Web.

- Boyle, Michael, Mark Verstegen, and Alwyn Cosgrove. Advances in Functional Training: Training Techniques for Coaches, Personal Trainers and Athletes. N.p.: On Target Publications, 2015. Print.

- Bryanton, Megan A., Jason P. Carey, Michael D. Kennedy, and Loren Z.f. Chiu. “Quadriceps Effort during Squat Exercise Depends on Hip Extensor Muscle Strategy.” Sports Biomechanics 14.1 (2015): 122-38. Web.

- Glassbrook, Daniel J., Scott R. Brown, Eric R. Helms, J. Scott Duncan, and Adam G. Storey. “The High-bar and Low-bar Back-squats.” Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research (2017): 1. Web.

- Gorsuch, J., J. Long, K. Miller, K. Primeau, S. Rutledge, A. Sossong, and J. J. Durocher. “The Effect of Squat Depth on Multiarticular Muscle Activation in Collegiate Cross-country Runners.” Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research. U.S. National Library of Medicine, Sept. 2013. Web.

- Hartmann, Hagen, Klaus Wirth, and Markus Klusemann. “Analysis of the Load on the Knee Joint and Vertebral Column with Changes in Squatting Depth and Weight Load.” Sports Medicine 43.10 (2013): 993-1008. Web.

- Nessler, Trent, Linda Denney, and Justin Sampley. “ACL Injury Prevention: What Does Research Tell Us?” Current Reviews in Musculoskeletal Medicine 10.3 (2017): 281-88. Web.

- Salem, G. J., R. Salinas, and F. V. Harding. “Bilateral Kinematic and Kinetic Analysis of the Squat Exercise after Anterior Cruciate Ligament Reconstruction.” Archives of Physical and Medical Rehabilitation 1211-6 84.8 (2003): n. pag. Print.

- Wahlstedt, Charlotta, and Eva Rasmussen-Barr. “Anterior Cruciate Ligament Injury and Ankle Dorsiflexion.” Knee Surgery, Sports Traumatology, Arthroscopy : Official Journal of the ESSKA, U.S. National Library of Medicine, Nov. 2015, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24923690.

Photo Credit: Halfpoint/iStock

READ MORE:

RECOMMENDED FOR YOU

MOST POPULAR

Why I Stopped Back Squatting My Athletes

This article is for team sport athletes, not powerlifters.

I don’t believe the Barbell Back Squat is the best way to train team sport athletes. I know that might sound crazy, but I ask that you read with an open mind and consider the points I raise here. The nuances of team sport athletics require thinking outside the box of traditional strength training. My argument that the Barbell Back Squat is not the best choice for most team sport athletes revolves around four key points: Torso Angle, Muscle Activation, Ankle Mobility and Safety. I’m writing this as a strength and conditioning coach who trains high school athletes, mostly of the team sport variety. Some of the issues I raise here might not necessarily apply to a “perfect” back squatter, but the reality is that the overwhelming majority of team sport athletes are not perfect back squatters.

1. Torso Angle Too Far Forward

The location of the bar during the Back Squat forces the torso to come forward to keep the weight over the athlete’s mid foot. Athletes with great mobility are able to have a more vertical torso in the Back Squat, but the majority of athletes will need to hinge more at their hips to maintain balance over the mid foot. This significantly increases the load on the low back, which is one of the most important areas to protect when strength training.

Secondly, as the torso comes forward, this will cause contraction of the hamstrings, which will make it more difficult to get below parallel with proper form on your Squats. I will explain why this is so significant later on.

Approximate torso angles I typically see on Back Squat/Front Squat/Overhead Squat

I find the Back Squat often leads team sport athletes to have too forward a torso angle for my liking.

2. Glutes Not Getting Involved

Many coaches tout the Back Squat for its ability to engage all the muscles of the lower body in one coordinated movement. While in theory that is true, for the majority of athletes it’s not quite accurate to what happens in practice. As I stated above, the forward torso angle many athletes demonstrate in the Back Squat often makes it more difficult to get below parallel. The reason this matters is that research has shown that the glutes don’t see significant activation until the athlete gets below parallel. This means that the athlete is likely relying almost entirely on the hamstrings for hip extension.

Hamstring-Dependent Back Squat vs Glute-Dependent Back Squat

Why does it matter if an athlete has strong hamstrings and weak, inactive glutes? The hamstrings work at both the knee (as flexors) and the hip (as synergists to extension). When the hamstrings are forced to be prime movers both at the hip and knee, you increase the risk of sustaining a hamstring strain. Inactive glutes have also been linked to other common athletic injuries, such as Patellar Tendonitis and ACL/MCL Tears. For this reason, I personally will not use any exercise that increases the hamstrings role at the hip at the expense of glute function. In my eyes, the Back Squat is the most common culprit of this.

3. The Ripple Effect of Poor Ankle Mobility

I get mocked mercilessly by my athletes for my love of ankle mobility. However, there’s a reason I obsess over it so much. The ankle is the first major link in the kinetic chain. Connected to the foot, it is the first major joint to contact the ground during land-based athletic movements like running and jumping. If there is something wrong with the ankle, it is going to cause issues all the way up the chain. Sufficient ankle mobility is crucial for athletic performance and injury prevention. Along with improper glute function, research has begun to show correlations between limitations in ankle dorsiflexion and non-contact ACL Tears. The reason ankle mobility can be a strike against the Back Squat is because the exercise is perhaps the only squat variation that allows you to compensate for a lack of ankle mobility.

In the Back Squat, athletes can hinge at their torso to compensate or work around limited movement at the ankle. Instead of training the ankle to move, this actually works to reduce overall motion at the ankle. I see too many athletes fall victim to something that looks like this on the Back Squat, where they compensate for a lack of ankle mobility by sitting back to load the low back and depend on the strength of the hamstrings rather than the glutes (compared to the level of ankle mobility I often see in a Front Squat) :

As you see in the Front and Overhead Squat Images, there’s a lot more ankle mobility being displayed. Again, these are not issues with a “perfect” back squatter, but they are issues I frequently see crop up for team sport athletes.

4. Not as Safe as You Might Think

For any strength and conditioning coach, every programmed exercise must be weighed on the risk-reward continuum. For example; while the Single-Arm, Single-Leg Overhead Squat may have plenty of benefits for strength, stability, balance and coordination, it’s probably not the safest option. In my opinion, the risks outweigh the rewards. I tell my athletes that there will always come a point that you will fail in the weight room. As a strength coach, I need to take precautions for when that occurs.

If an athlete fails on the Back Squat, things can get risky pretty quickly. Yes, you can use pins—but many high school weight rooms don’t have them. Yes, spotters will make it less dangerous, but most high school students have a tough time even knowing when they’re going to require a spotter. I also have very little faith in a high school male taking seriously the importance of their role as a spotter, which puts both the lifter and the spotter at risk of injury. With highly trained athletes who know their limits and who are working in an environment where pins are available and every spotter takes their job seriously, the risk is a lot lower. But in your average high school weight room, the reality is that the Back Squat is not the safest of exercises.

The combination of all four issues led me to seriously rethink if it was worthing having the Back Squat in my programs. But if not the Back Squat, then what? For me, the answer I came to was the Front Squat.

Why I Love the Front Squat for my Athletes

I personally believe the Front Squat is superior in all four categories outlined above while maintaining all the benefits of a bilateral movement. It’s a much safer variation, because when an athlete fails, they simply “bail” the bar in front of them. A spotter is completely superfluous; you simply don’t need one during front squatting. The Front Squat, as shown in the photos above, also has a more vertical torso angle, which reduces the load on the lumbar spine. Due to that torso angle, hip movement is more easily driven by the glutes than it is the hamstrings. This is highly advantageous for athletes who struggle with firing their glutes. I also believe it’s much easier to get below parallel in the Front Squat, which is where glute activity really occurs in squatting.

The Front Squat isn’t nearly as technical as the Overhead Squat and it’s more conducive to good positions than the Back Squat. Lastly, it is nearly impossible to compensate for a lack of ankle mobility in a Front Squat. If the athlete lacks sufficient ankle dorsiflexion, their torso falls forward, causing the bar to roll off of their shoulders. The athlete is forced to address their mobility issues instead of compensating for them. While most athletes cannot Front Squat quite as much as they can Back Squat, you can still load it plenty heavy. And since it’s much harder to “cheat” a Front Squat than a Back Squat, athletes are more likely to use appropriate weights. Quite simply, it’s a lot harder to mess up a Front Squat than it is a Back Squat.

For these reasons, I believe the Front Squat is the superior bilateral squat. Do I still Back Squat with my athletes? Yes, but only as a change-of-pace lift in the offseason. Never during the preseason or in season. In my experience, the risk is simply not worth the reward to do them more often than that, as the Front Squat accomplishes what I want to accomplish in a safer, more effective manner.

References:

- Barton, Christian J., Simon Lack, Peter Malliaras, and Dylan Morrissey. “Gluteal Muscle Activity and Patellofemoral Pain Syndrome: A Systematic Review.” British Journal of Sports Medicine 47.4 (2012): 207-14. Web.

- Boyle, Michael, Mark Verstegen, and Alwyn Cosgrove. Advances in Functional Training: Training Techniques for Coaches, Personal Trainers and Athletes. N.p.: On Target Publications, 2015. Print.

- Bryanton, Megan A., Jason P. Carey, Michael D. Kennedy, and Loren Z.f. Chiu. “Quadriceps Effort during Squat Exercise Depends on Hip Extensor Muscle Strategy.” Sports Biomechanics 14.1 (2015): 122-38. Web.

- Glassbrook, Daniel J., Scott R. Brown, Eric R. Helms, J. Scott Duncan, and Adam G. Storey. “The High-bar and Low-bar Back-squats.” Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research (2017): 1. Web.

- Gorsuch, J., J. Long, K. Miller, K. Primeau, S. Rutledge, A. Sossong, and J. J. Durocher. “The Effect of Squat Depth on Multiarticular Muscle Activation in Collegiate Cross-country Runners.” Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research. U.S. National Library of Medicine, Sept. 2013. Web.

- Hartmann, Hagen, Klaus Wirth, and Markus Klusemann. “Analysis of the Load on the Knee Joint and Vertebral Column with Changes in Squatting Depth and Weight Load.” Sports Medicine 43.10 (2013): 993-1008. Web.

- Nessler, Trent, Linda Denney, and Justin Sampley. “ACL Injury Prevention: What Does Research Tell Us?” Current Reviews in Musculoskeletal Medicine 10.3 (2017): 281-88. Web.

- Salem, G. J., R. Salinas, and F. V. Harding. “Bilateral Kinematic and Kinetic Analysis of the Squat Exercise after Anterior Cruciate Ligament Reconstruction.” Archives of Physical and Medical Rehabilitation 1211-6 84.8 (2003): n. pag. Print.

- Wahlstedt, Charlotta, and Eva Rasmussen-Barr. “Anterior Cruciate Ligament Injury and Ankle Dorsiflexion.” Knee Surgery, Sports Traumatology, Arthroscopy : Official Journal of the ESSKA, U.S. National Library of Medicine, Nov. 2015, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24923690.

Photo Credit: Halfpoint/iStock

READ MORE: