Why Your Shoulder Pain Isn’t Usually a Shoulder Problem

The common traditional culprits for shoulder pain are the rotator cuff, AC joint and scapula. Many physical therapists, trainers and doctors will look at your shoulder when you have pain there. They will prescribe “rotator cuff” strengthening exercises, shoulder capsule stretches, and tell you to take time off.

However, this is a limited and unfortunately short-sighted approach for fixing shoulder pain in the long run.

Why? Because pain needs a global approach. The body is not a series of isolated joints and parts. If we’ve learned anything in recent advancements in treating the human body, it’s that everything is connected, and you cannot separate one part of the body from another.

How Does Shoulder Pain Develop?

One thing the traditional approach has right is that the rotator cuff and scapula are out of position, weak or not firing in the correct sequence. But I’m not really worried about that part until we address something much more important: The ribcage.

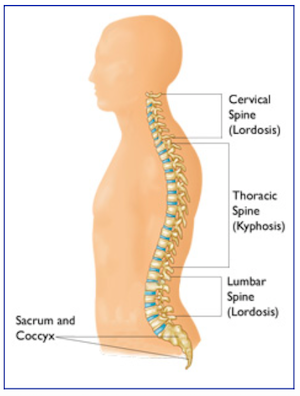

Take a look at the images above. Notice how the normal, healthy human spine has a degree of thoracic kyphosis, or flexion. The shoulder blade is a concave bone that must sit on a convex ribcage for it to glide, rotate and move effectively.

The problem is, many (I would argue the vast majority of) people have an extension problem. When this happens, the pelvis tips forward and is stuck there. This causes the thoracic spine to flatten out and the thoracic spine loses its necessary flexion, which leads to the shoulder blade not being able to sit correctly on a convex ribcage.

When this happens, the scapula has to compensate for a lack of normal mobility. The result is what you would see in a normal person with shoulder dysfunction:

The above example is extreme, but illustrates my point of how a scapula will move to gain any kind of leverage to allow for shoulder mobility. When compensation develops, pain often follows.

So yes, it could be a rotator cuff problem. Or an AC joint problem. But it all started at the ribcage.

What Can I Do?

Step one: Fix your breathing.

This might sound strange, but breathing really is everything. We take over 20,000 breaths every day. It has a direct relationship with your posture.

Good breathing involves full expansion of the ribcage, particularly in the back, or posterior, ribcage. What most people don’t realize is that a huge chunk of your lungs are in the back portion of your ribcage.

If we cannot expand that area due to excessive extension, the ribcage cannot maintain a convex structure. Thus, the scapula can’t sit on it.

To fix breathing, it is imperative to work on getting thoracic flexion while we inhale and maintain it while we exhale. If you can’t feel your posterior ribcage expand upon inhalation, it is not expanding. It is that simple.

Also, we must feel our abdominals, especially our obliques, when we exhale. This will assist us in restoring thoracic flexion as the obliques are responsible for pulling the anterior ribcage down and pelvis out of extension.

Here is an example exercise:

- Stand facing away from a door, and place your heels 7-10 inches from the wall.

- Stand up straight with a ball between your knees, and feet shoulder-width apart.

- Bring your arms out in front of you as you round out your back, performing a pelvic tilt so your lower back (mid-back and down) is flat on the wall.

- Squat slightly as you squeeze the ball.

- Keeping your lower back flat on the wall, inhale through your nose.

- As you exhale through your mouth, reach your arms forward and down so your upper back comes off the wall (your lower back should stay flat on the wall).

- Hold your arms steadily in this position (reach), as you inhale through your nose again and expand your upper back. You should feel a stretch in your upper back.

- Exhale and reach farther forward. You should feel the muscles on the front of your thighs and outer abdominals engage.

- Repeat this breathing sequence for a total of 4-5 deep breaths, in through your nose and out through your mouth.

- Slowly stand up by pushing through your heels, keeping your lower back flat on the wall.

- Relax and repeat 4 more times.

(Technique used with permission. Copyright © Postural Restoration Institute®2020. www.posturalrestoration.com)

After that is taken care of, we can clear up any rotator cuff or AC joint imbalances.

However, nothing will stick until we solve the root cause of the shoulder pain. That is why so many people fail to keep their shoulders anything more than temporarily healthy after an injury.

Photo Credit: djiledesign/iStock

READ MORE:

RECOMMENDED FOR YOU

Why Your Shoulder Pain Isn’t Usually a Shoulder Problem

The common traditional culprits for shoulder pain are the rotator cuff, AC joint and scapula. Many physical therapists, trainers and doctors will look at your shoulder when you have pain there. They will prescribe “rotator cuff” strengthening exercises, shoulder capsule stretches, and tell you to take time off.

However, this is a limited and unfortunately short-sighted approach for fixing shoulder pain in the long run.

Why? Because pain needs a global approach. The body is not a series of isolated joints and parts. If we’ve learned anything in recent advancements in treating the human body, it’s that everything is connected, and you cannot separate one part of the body from another.

How Does Shoulder Pain Develop?

One thing the traditional approach has right is that the rotator cuff and scapula are out of position, weak or not firing in the correct sequence. But I’m not really worried about that part until we address something much more important: The ribcage.

Take a look at the images above. Notice how the normal, healthy human spine has a degree of thoracic kyphosis, or flexion. The shoulder blade is a concave bone that must sit on a convex ribcage for it to glide, rotate and move effectively.

The problem is, many (I would argue the vast majority of) people have an extension problem. When this happens, the pelvis tips forward and is stuck there. This causes the thoracic spine to flatten out and the thoracic spine loses its necessary flexion, which leads to the shoulder blade not being able to sit correctly on a convex ribcage.

When this happens, the scapula has to compensate for a lack of normal mobility. The result is what you would see in a normal person with shoulder dysfunction:

The above example is extreme, but illustrates my point of how a scapula will move to gain any kind of leverage to allow for shoulder mobility. When compensation develops, pain often follows.

So yes, it could be a rotator cuff problem. Or an AC joint problem. But it all started at the ribcage.

What Can I Do?

Step one: Fix your breathing.

This might sound strange, but breathing really is everything. We take over 20,000 breaths every day. It has a direct relationship with your posture.

Good breathing involves full expansion of the ribcage, particularly in the back, or posterior, ribcage. What most people don’t realize is that a huge chunk of your lungs are in the back portion of your ribcage.

If we cannot expand that area due to excessive extension, the ribcage cannot maintain a convex structure. Thus, the scapula can’t sit on it.

To fix breathing, it is imperative to work on getting thoracic flexion while we inhale and maintain it while we exhale. If you can’t feel your posterior ribcage expand upon inhalation, it is not expanding. It is that simple.

Also, we must feel our abdominals, especially our obliques, when we exhale. This will assist us in restoring thoracic flexion as the obliques are responsible for pulling the anterior ribcage down and pelvis out of extension.

Here is an example exercise:

- Stand facing away from a door, and place your heels 7-10 inches from the wall.

- Stand up straight with a ball between your knees, and feet shoulder-width apart.

- Bring your arms out in front of you as you round out your back, performing a pelvic tilt so your lower back (mid-back and down) is flat on the wall.

- Squat slightly as you squeeze the ball.

- Keeping your lower back flat on the wall, inhale through your nose.

- As you exhale through your mouth, reach your arms forward and down so your upper back comes off the wall (your lower back should stay flat on the wall).

- Hold your arms steadily in this position (reach), as you inhale through your nose again and expand your upper back. You should feel a stretch in your upper back.

- Exhale and reach farther forward. You should feel the muscles on the front of your thighs and outer abdominals engage.

- Repeat this breathing sequence for a total of 4-5 deep breaths, in through your nose and out through your mouth.

- Slowly stand up by pushing through your heels, keeping your lower back flat on the wall.

- Relax and repeat 4 more times.

(Technique used with permission. Copyright © Postural Restoration Institute®2020. www.posturalrestoration.com)

After that is taken care of, we can clear up any rotator cuff or AC joint imbalances.

However, nothing will stick until we solve the root cause of the shoulder pain. That is why so many people fail to keep their shoulders anything more than temporarily healthy after an injury.

Photo Credit: djiledesign/iStock

READ MORE: